Criminal Records

Currently, one in three American adults – about 78 million people – have a criminal record. Many of these people have just been arrested or charged, but were never convicted, while many other have been convicted of minor, non-violent crimes. These criminal records often stay with people for their entire life.

There has been a long-standing controversy about the negative consequences that such criminal records have on people’s ability to become employed, get housing, and vote.

In some cases, these negative consequences are due to the actions of the government and public institutions such as public housing authorities and licensing boards. Across the country, there are over 44,000 rules that put up barriers for people with criminal records, and restrict them from employment, licensing, public housing, voting and other activities.

In other cases, the negative consequences of a criminal record are the result of discrimination by private employers, who may see people as too much of a liability. Studies have found that this discrimination falls hardest on racial minorities with criminal records.

To address these concerns, several proposals have been introduced by Members of Congress to remove these barriers. Some of these proposals would prohibit employers, licensing boards and public housing authorities from disqualifying people – rejecting applicants, firing employees or evicting tenants – based solely on certain criminal records. Other proposals would make it easier for records of arrests or non-violent drug offenses to be sealed from the public. And another would restore voting rights to people with felony records once their prison sentences have been completed.

These proposals have appeared in:

- Next Step Act of 2019 by Rep. Bonnie Watson-Coleman (H.R. 1893) and Sen. Cory Booker (S. 697)

- Fair Chance at Housing Act of 2019 by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (H.R. 3685) and former Sen. Kamala Harris (S. 2076)

- Jobs and Justice Act of 2020 by Rep. Karen Bass (H.R. 8352)

- Democracy Restoration Act of 2021 by Sen. Ben Cardin (S. 481)

- For the People Act of 2021 by Rep. John Sarbanes (H.R. 1) and Sen. Jeff Merkley (S. 1)

- National sample: 2,487 registered voters

- Margin of error: +/- 2.0%

- Fielded: Feb 12-22, 2021

- Survey Questionnaire (PDF)

The survey covered major provisions from:

- Next Step Act of 2019 by Rep. Bonnie Watson-Coleman (H.R. 1893) and Sen. Cory Booker (S. 697)

- Fair Chance at Housing Act of 2019 by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (H.R. 3685) and former Sen. Kamala Harris (S. 2076)

- Jobs and Justice Act of 2020 by Rep. Karen Bass (H.R. 8352)

- Democracy Restoration Act of 2021 by Sen. Ben Cardin (S. 481)

- For the People Act of 2021 by Rep. John Sarbanes (H.R. 1) and Sen. Jeff Merkley (S. 1)

Proposals with bipartisan support discussed below include:

- Four for limiting the use of certain criminal records by employers and licensing boards as the basis for rejecting an applicant or firing an employee

- One for providing protection from liability to employers who knowingly hire people with criminal records

- One for limiting the use of certain criminal records by public Housing Authorities as the basis for rejecting an applicant or evicting a tenant

- Two for sealing criminal records for arrests that do not result in convictions, and convictions for non-violent drug offenses

- One for reinstating the right to vote for felons who have served their prison sentence

Respondents were presented the following briefing on criminal records, including how many people have one, and their negative effects on employment, housing and voting rights: As you may know, when someone is arrested, this creates a criminal record for that person. This record remains in place if, after being arrested, the person is never charged with a crime, the charges are dropped, or if they are tried and not found guilty. The record also remains in place after someone serves their sentence. Currently, there is a controversy about the negative consequences for people with criminal records on their ability to get employment, to get housing, and to vote. In some cases, these negative consequences are due to the actions of governments, public housing authorities, and licensing boards. In other cases, they are due to private employers discriminating against people with criminal records. Currently, one in three American adults – about 78 million people – have a criminal record. Of these, about 14 million people have been convicted of a felony – that is a crime that can be serious and may include violence. The remaining 64 million people include: People who were found guilty of a minor offense or a misdemeanor. With a few rare exceptions, these are nonviolent offenses. Examples are possession of drugs, shoplifting, public intoxication, trespassing, vandalism, and speeding. People who have not been convicted of any crime or offense. If someone is arrested but is not charged, or is charged but found not guilty, they also have a criminal record.

EMPLOYMENT & LICENSING |

|

|

Respondents were presented a briefing on how criminal records affect a person’s chances to become employed or receive a license: There are local, state, and federal rules that disadvantage people with criminal records when applying for jobs or disqualify them from certain lines of work. Currently, there are at least 30,000 such rules across the country. They can also face disadvantages in the event that employers discriminate against them for having a criminal record. Some states have passed laws that seek to reduce employment discrimination against those with criminal records. They were also informed that: This use of criminal records is of concern because some people who are discriminated against due to their criminal records:

Also, studies show employers are more likely to reject applicants who are racial minorities based on their criminal records. Respondents then evaluated specific proposals from the Next Step Act of 2019 to reform how criminal records can be used by employers and licensing boards. |

|

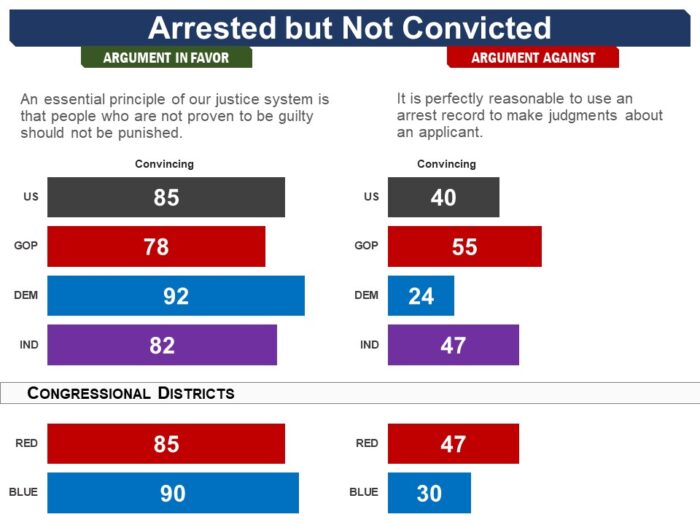

Respondents were first introduced to the specific proposal, “to prohibit licensing boards and employers from disqualifying a person because they were arrested but not charged, or charged with a crime but found not guilty.” This proposal was based on the Next Step Act of 2019 (H.R. 1893, S. 697). The argument in favor of this proposal was found convincing by a large bipartisan majority of 85%, including nearly eight in ten Republicans and over nine in ten Democrats. While the argument against was found convincing by less than half (40%), including just a quarter of Democrats, but a modest majority of Republicans. |

|

Respondents were presented the proposal, “to prohibit licensing boards and employers from disqualifying a person because they have been convicted of a petty, non-violent offense. This can include littering, jaywalking, failing to pay a parking ticket, or loitering.” This proposal was based on the Next Step Act of 2019 (H.R. 1893, S. 697). The argument in favor was found convincing by a large bipartisan majority of over eight in ten, including three quarters of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The argument against did substantially worse, with less than four in ten finding it convincing, including less than half of Republicans and just a quarter of Democrats. |

|

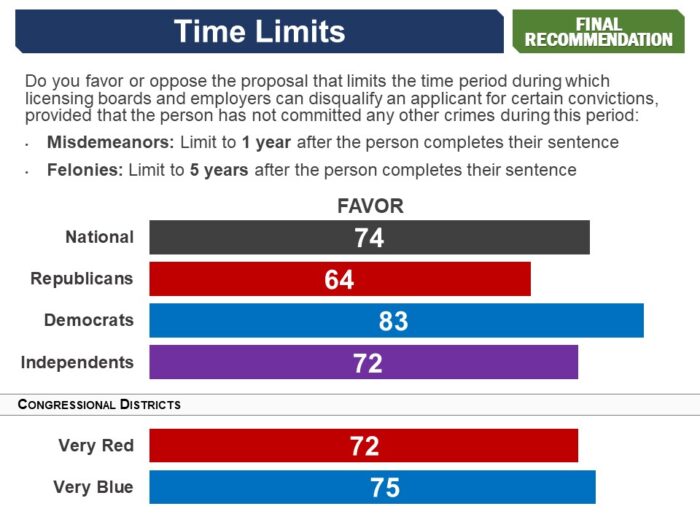

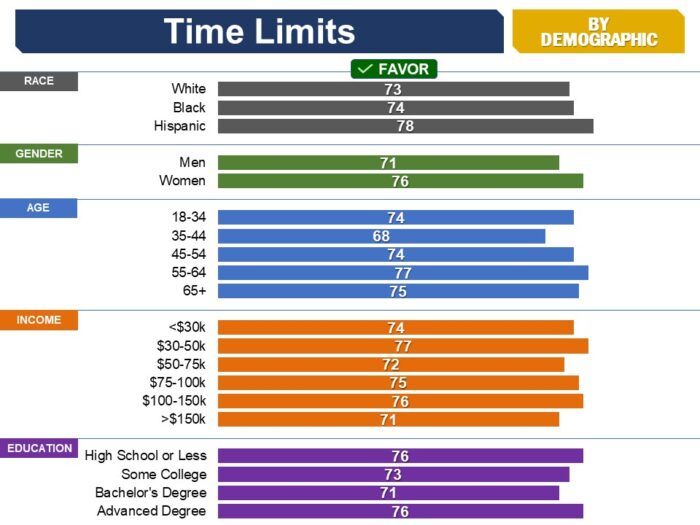

To address the negative employment effects of past convictions, Members of Congress have introduced legislation to limit the time period during which employers and licensing boards can use such convictions as the basis for rejecting a job or license applicant, or firing an employee. Respondents were presented a proposal based on the Next Step Act of 2019 (H.R. 1893, S. 697). First, respondents were informed how more “substantial crimes”, such as misdemeanors and felonies, are defined:

They were told that, “Currently, licensing boards and employers in many states can disqualify a person because they have been convicted of such a misdemeanor or felony, and some have a policy of doing so automatically, irrespective of when the crime was committed.” They were then introduced to the proposal: ...to limit the period of time during which licensing boards and employers can disqualify an applicant for certain convictions, provided that the person has not committed any other crimes during this period:

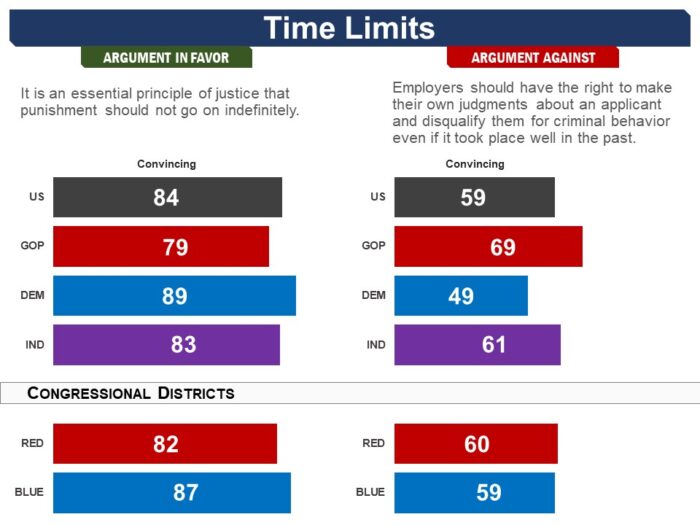

The first argument in favor was found convincing by a very large bipartisan majority of 84%, including eight in ten Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The argument against was found convincing by a majority of nearly six in ten, including seven in ten Republicans, but just under half of Democrats (49%). Status of Legislation |

|

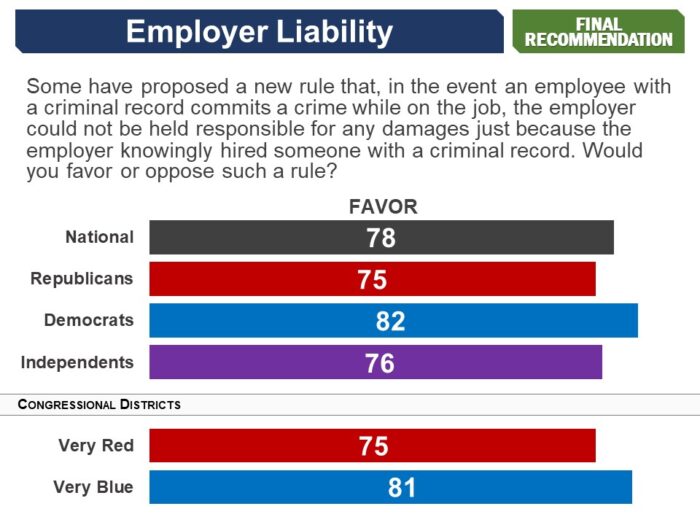

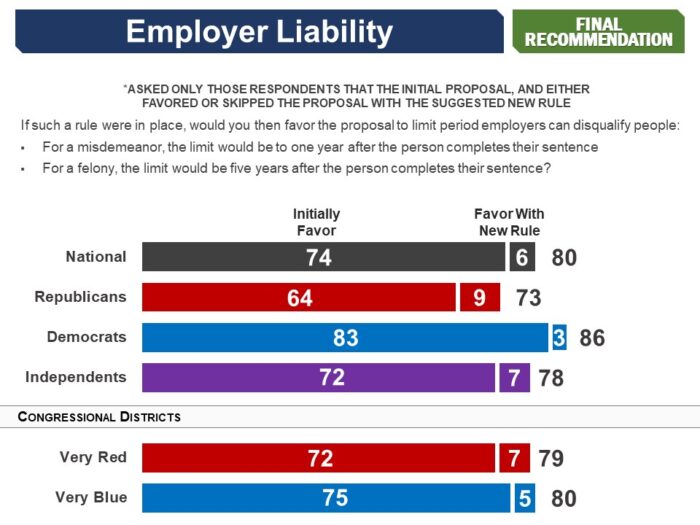

Some employers, as well as several Chambers of Commerce, have argued against the above proposals to restrict the use of certain criminal records as the basis for disqualifying job applicants. Their argument is based on the concern that, when an employer hires a person with a criminal record, they are more likely to be held liable if that employee commits a crime while on the job, because the employer knowingly hired a person with a criminal past. To address this concern, Chambers of Commerce have proposed a new rule to shield employers from such liability. Respondents were first introduced to this idea of employer liability as a concern in the argument against the above proposal for time limits. Of all con arguments for all proposals, it was the one found convincing by the largest number. Six in ten (59%) found convincing the argument that prohibiting employers from discriminating based on old convictions would pose liability issues for employers, including seven in ten Republicans, and nearly half of Democrats (47%). The possible new rule was presented to respondents as follows: Some people have proposed a new rule that, in the event an employee with a criminal record commits a crime while on the job, the employer could not be held responsible for any damages just because the employer knowingly hired someone with a criminal record. A large bipartisan majority of 78% favored this new rule, including three quarters of Republicans and over eight in ten Democrats. If such a rule were in place would you then favor the proposal to: Limit the period of time during which licensing boards and employers can disqualify an applicant for certain convictions, provided that the person has not committed any other crimes during this period:

Out of the total sample, with the employer liability provision in place, six percent changed their position to favoring time limits, including nine percent of Republicans and three percent of Democrats. Combining these responses with the initial responses to the time limits proposal, support for the proposal rose to eight in ten, including 73% of Republicans and 86% of Democrats. |

|

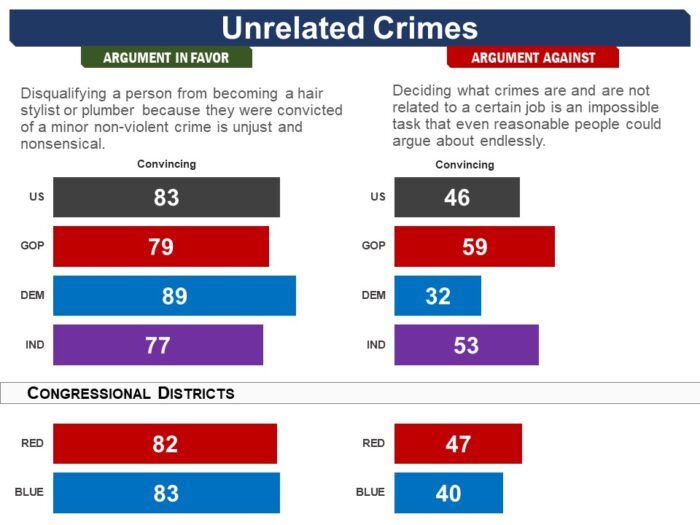

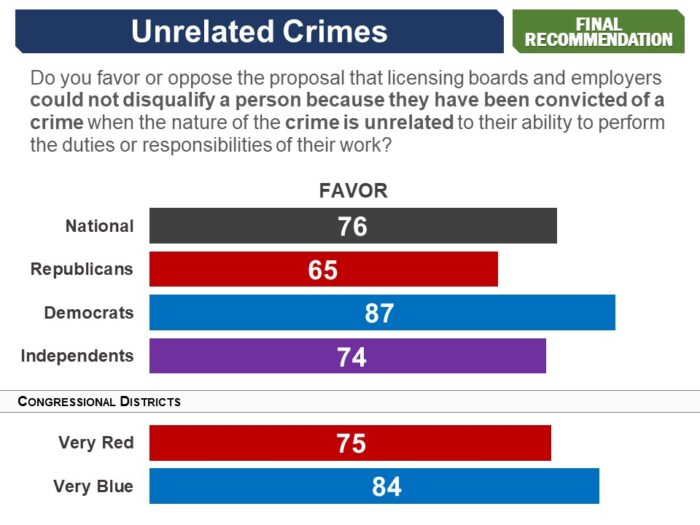

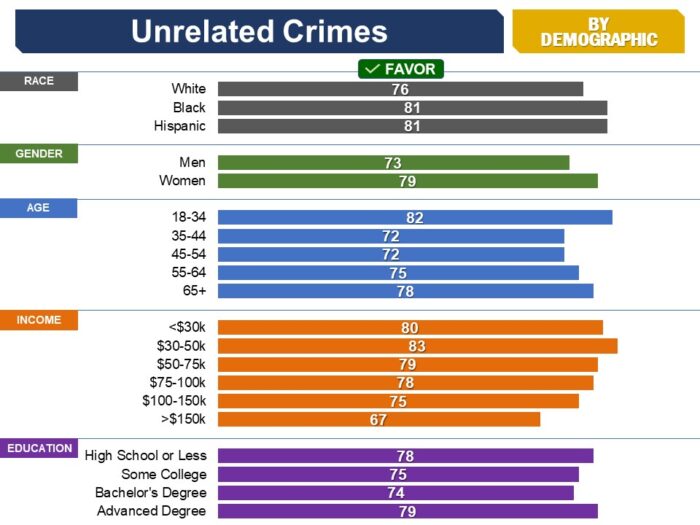

Respondents were introduced to the following proposal, based on the Next Step Act of 2019 (H.R. 1893, S. 697): Licensing boards and employers could not disqualify a person because they have been convicted of just any crime. They would have to establish that the crime is clearly related to one’s ability to perform the duties or responsibilities of their work. For example, someone previously convicted of drunk driving could be disqualified from having a job as a driver. This rule has already been adopted in over half of states and the proposal, now, is to make it a federal law. The argument in favor was found convincing by a very large bipartisan majority of 83%, including nearly eight in ten Republicans and about nine in ten Democrats. The argument against was found convincing by less than half (46%), including just one in three Democrats, but about six in ten Republicans. |

|

PUBLIC HOUSING |

|

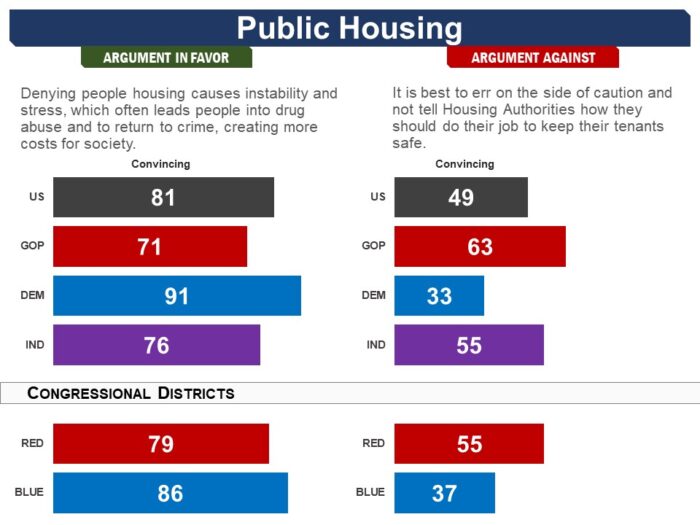

In order to address the negative effects that criminal records can have on people’s ability to secure public housing, Members of Congress have introduced a proposal to restrict the use of certain criminal records by public Housing Authorities as the basis for rejecting applicants or evicting tenants. The proposal presented to respondents was based on the Fair Chance Housing Act of 2019 (H.R. 3685, S. 2076). Respondents were first briefed on how public housing works: Currently, there are about 9.4 million people living in public housing. These are homes that are only available to low-income people, or those with disabilities. The rent for public housing is limited to about 30 percent of a person’s income. State and Federal government provide subsidies to cover the rest of the cost. Though public housing is subsidized by the government, the public housing program is managed by independent organizations known as “Housing Authorities.” They were then introduced to how criminal records can and do affect peoples’ ability to receive, or continue to receive, such housing: Housing Authorities can and do disqualify people based on their criminal record--by rejecting their application or evicting them. Studies show that:

This use of criminal records is of concern because some people who are discriminated against due to their criminal records:

They were presented the specific proposal, as follows: Housing Authorities would not be allowed to disqualify a person from public housing because they:

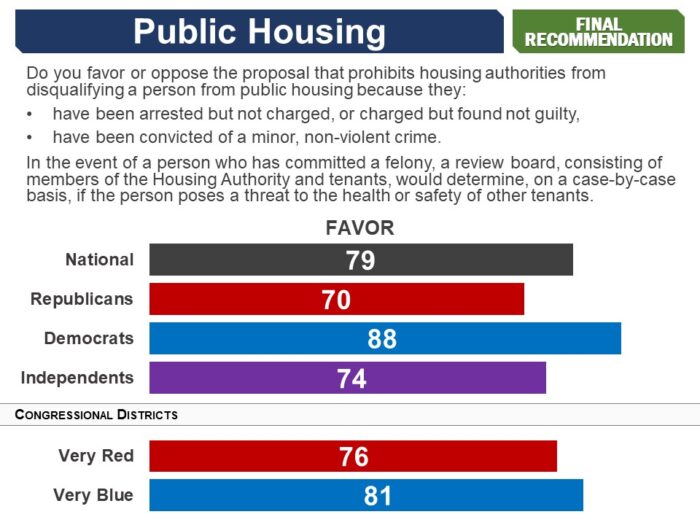

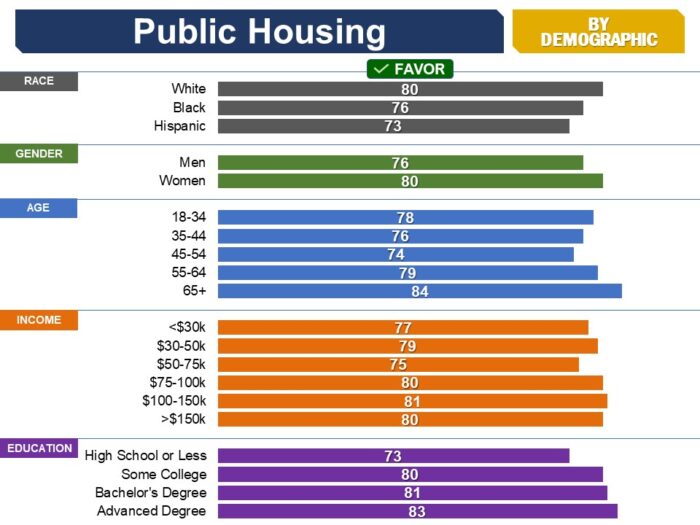

In the event of a person who has committed a felony, a review board, consisting of members of the Housing Authority and tenants, would determine, on a case-by-case basis, if the person poses a threat to the health or safety of other tenants. The argument in favor was found convincing by a very large bipartisan majority of eight in ten (81%), including seven in ten Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The argument against did less well, with just under half finding it convincing (49%), including just one in three Democrats, but a large majority of Republicans (63%). Out of the total sample, ten percent were in favor, including 18% of Republicans and four percent of Democrats. Status of Legislation |

|

SEALING CRIMINAL RECORDS |

|

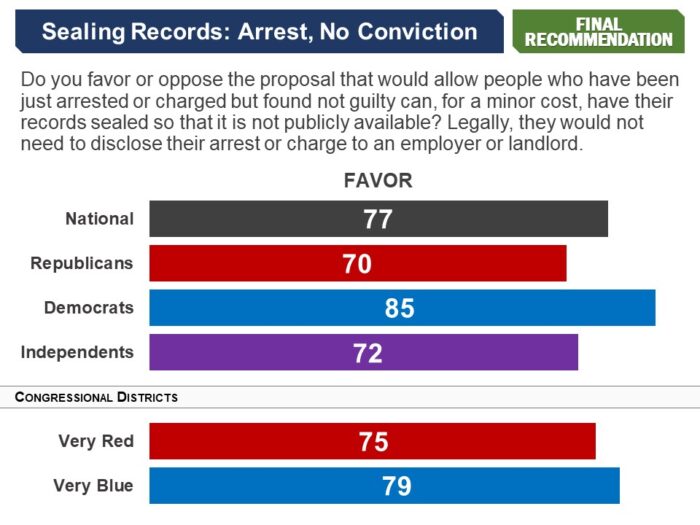

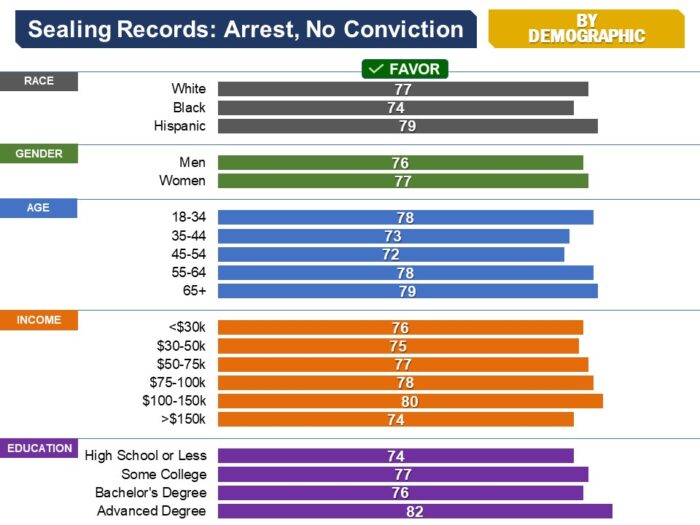

Respondents were presented the following proposal, based on the Next Step Act of 2019 (H.R. 1893, S. 697): People who have been arrested but not charged, or charged but found not guilty, can, for a minor cost, have their records sealed so that it is not public and thus not available to potential employers or landlords. Legally, they would not need to disclose their arrest or charge to an employer or landlord. The argument in favor was found convincing by a very large bipartisan majority of 85%, with little partisan variation (Republicans 84%, Democrats 89%). The argument against did substantially worse, with just four in ten finding it convincing, including under three in ten Democrats. A bare majority of Republicans (52%) found it convincing. |

|

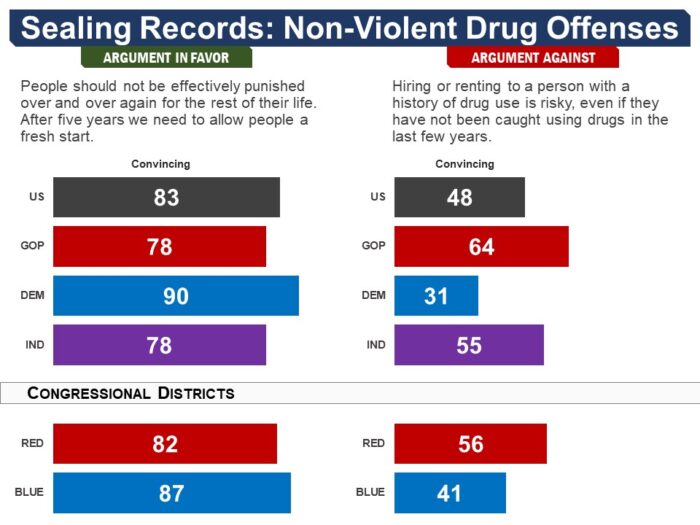

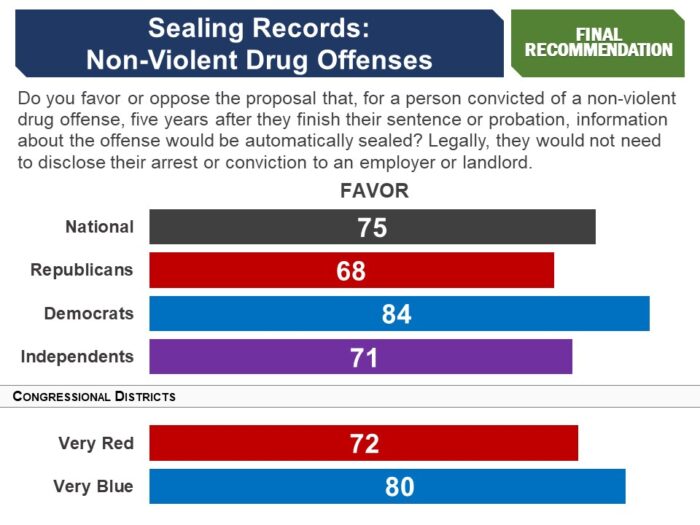

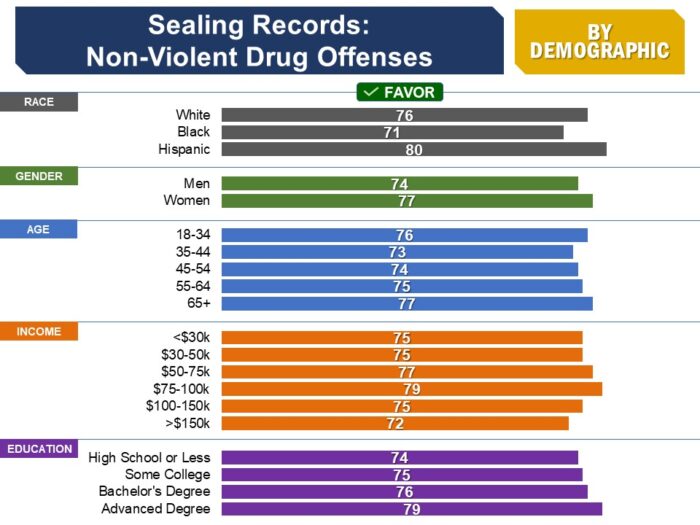

Respondents were presented the following proposal, based on the Next Step Act of 2019 (H.R. 1893, S. 697): for a person convicted of a non-violent drug offense, five years after they finish their sentence or probation, information about the offense would be automatically sealed. Legally, they would not need to disclose their arrest or conviction to an employer or landlord. The argument in favor was found convincing by a very large bipartisan majority of 83%, including 78% of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. Less than half (48%) found the counter argument convincing, including just three in ten Democrats. Among Republicans, nearly two thirds (64%) found it convincing. Some people think that someone with a non-violent drug offense should not have to disclose this information. Others think that they should have to disclose it for a limited number of years, or forever. Do you think after someone has completed their sentence for a nonviolent drug offense they:

Overall, the typical (median) respondent recommended that non-violent drug offenses should have to be disclosed for a maximum of three years. The median Democrat recommended that such an offense should never have to be disclosed; and the median Republican recommended a maximum of five years. Status of Legislation |

|

VOTING RIGHTS |

|

Members of Congress have introduced several pieces of legislation that would automatically restore voting rights to all people who lose their voting rights while incarcerated, and complete their prison sentence. Before being presented the proposal, respondents were provided a briefing on the issue of felon disenfranchisement: In nearly all states, people who have committed a felony lose their right to vote while they are in prison, and in some states, this can apply to those who have served time in prison for committing misdemeanors as well. In some states people who are no longer in prison continue to be barred from voting:

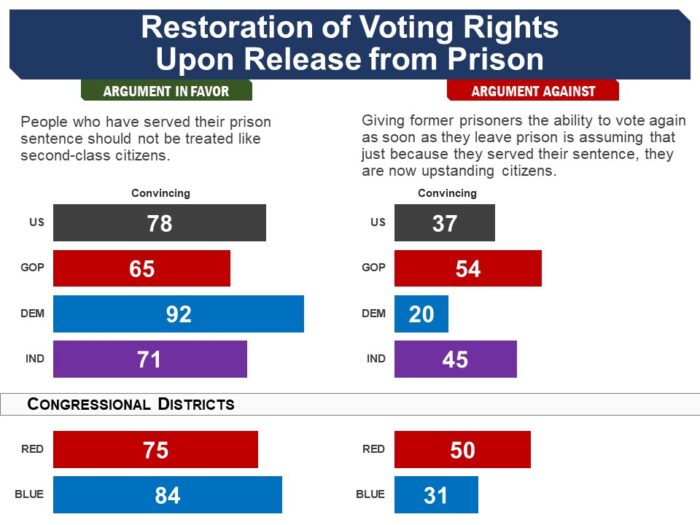

In some states, for some crimes, people can permanently lose the right to vote. Currently, there are nearly 6 million citizens who are not in prison but do not have the right to vote. They were then introduced to the specific proposal: A person who completes their prison sentence would have their right to vote in federal elections immediately restored. The first argument in favor was found convincing by a large bipartisan majority of 78%, including nearly two thirds of Republicans and over nine in ten Democrats. The argument against did substantially worse, with less than four in ten finding it convincing, including just two in ten Democrats, but a majority of Republicans (54%).

Polls in Kentucky and Florida have also found majority support for felon re-enfranchisement, including majority or plurality support among Republicans:

Status of Legislation The proposal is also in the Democracy Restoration Act of 2021 by Sen. Ben Cardin (S.481), which is part of the For the People Act (S.1). In the 116th Congress, the proposal was introduced in several bills:

|

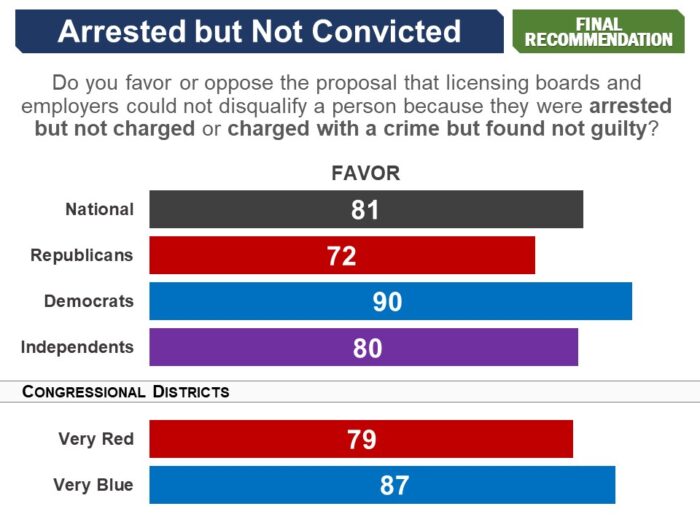

Asked for their final recommendation, a very large bipartisan majority of eight in ten (81%) favored the proposal, including 72% of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats.

Asked for their final recommendation, a very large bipartisan majority of eight in ten (81%) favored the proposal, including 72% of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats.

Status of Legislation

Status of Legislation

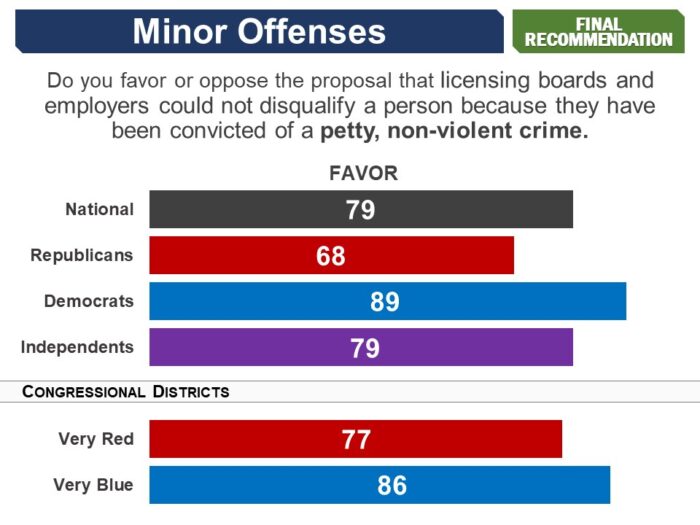

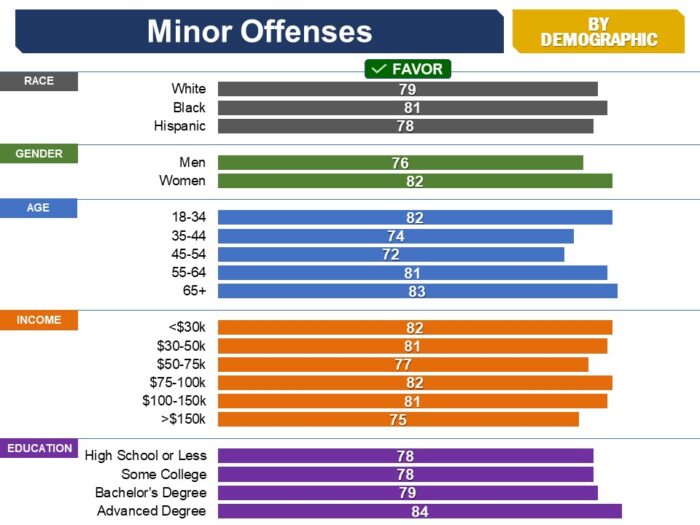

Asked for their final recommendation, eight in ten (79%) were in favor of the proposal, including over two thirds of Republicans (68%) and nine in ten Democrats (89%).

Asked for their final recommendation, eight in ten (79%) were in favor of the proposal, including over two thirds of Republicans (68%) and nine in ten Democrats (89%).

Status of Legislation

Status of Legislation

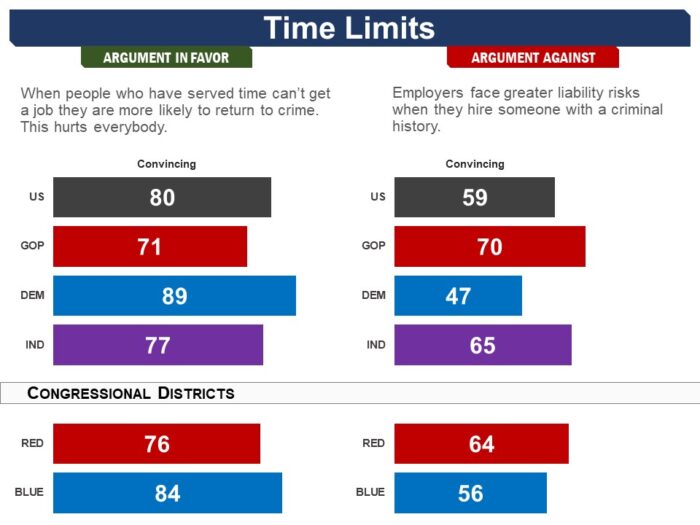

The second argument in favor was found convincing by eight in ten, including seven in ten Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The argument against was found convincing by around six in ten, including seven in ten Republicans, and nearly half of Democrats (47%).

The second argument in favor was found convincing by eight in ten, including seven in ten Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The argument against was found convincing by around six in ten, including seven in ten Republicans, and nearly half of Democrats (47%). Asked for their final recommendation, a large bipartisan majority of 74% were in favor, including 64% of Republicans and 83% of Democrats.

Asked for their final recommendation, a large bipartisan majority of 74% were in favor, including 64% of Republicans and 83% of Democrats.

As is discussed below in the section on employer liability, some respondents who initially opposed this proposal shifted to supporting it if employer’s were provided protection from liability for knowingly hiring someone with a criminal record.

As is discussed below in the section on employer liability, some respondents who initially opposed this proposal shifted to supporting it if employer’s were provided protection from liability for knowingly hiring someone with a criminal record.

To see whether the implementation of this new liability rule would have any effect on respondents’ support for the above proposal on time limit, those who opposed the proposal for limiting the time period during which employers can consider past misdemeanors and felonies, and favored the new liability rule were asked:

To see whether the implementation of this new liability rule would have any effect on respondents’ support for the above proposal on time limit, those who opposed the proposal for limiting the time period during which employers can consider past misdemeanors and felonies, and favored the new liability rule were asked:

Asked for their final recommendation, over three quarters (76%) favored this proposal, including 65% of Republicans and 87% of Democrats.

Asked for their final recommendation, over three quarters (76%) favored this proposal, including 65% of Republicans and 87% of Democrats.

Asked for their final recommendation, a very large bipartisan majority of nearly eight in ten (79%) were in favor, including seven in ten Republicans and 88% of Democrats.

Asked for their final recommendation, a very large bipartisan majority of nearly eight in ten (79%) were in favor, including seven in ten Republicans and 88% of Democrats.

Those who opposed the proposal were asked if they would favor a more limited version, which would, “allow Housing authorities to disqualify a person if they are convicted of a crime, whether it is major or minor. But they would not be able to disqualify a person if they were only arrested but not charged or charged but found not guilty.”

Those who opposed the proposal were asked if they would favor a more limited version, which would, “allow Housing authorities to disqualify a person if they are convicted of a crime, whether it is major or minor. But they would not be able to disqualify a person if they were only arrested but not charged or charged but found not guilty.”

Asked for their final recommendation, a large bipartisan majority of 77% were in favor, including seven in ten Republicans and 85% of Democrats.

Asked for their final recommendation, a large bipartisan majority of 77% were in favor, including seven in ten Republicans and 85% of Democrats.

Status of Legislation

Status of Legislation

Asked for their final recommendation, a large bipartisan majority of three in four favored the proposal, including 68% of Republicans and 84% of Democrats.

Asked for their final recommendation, a large bipartisan majority of three in four favored the proposal, including 68% of Republicans and 84% of Democrats.

Respondents were also given the opportunity to choose how long non-violent drug offenses should have to be disclosed. They were presented the question as follows:

Respondents were also given the opportunity to choose how long non-violent drug offenses should have to be disclosed. They were presented the question as follows:

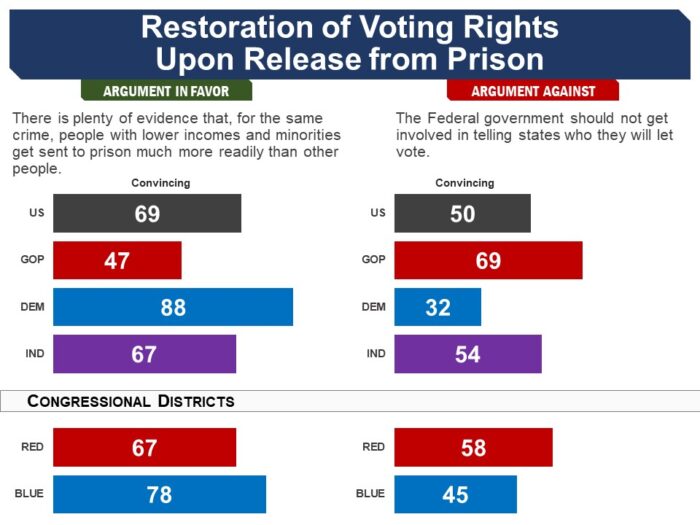

The second argument in favor was found convincing by a partisan majority of nearly seven in ten, including 88% of Democrats, but less than half of Republicans (47%). The argument against received a divided response, split along partisan lines. Half found it convincing, including 69% of Republicans but just 32% of Democrats.

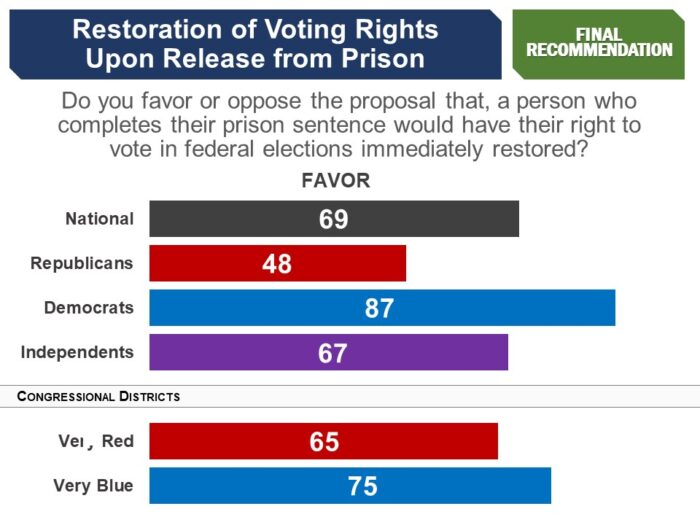

The second argument in favor was found convincing by a partisan majority of nearly seven in ten, including 88% of Democrats, but less than half of Republicans (47%). The argument against received a divided response, split along partisan lines. Half found it convincing, including 69% of Republicans but just 32% of Democrats.  Asked for their final recommendation, a majority of nearly seven in ten (69%) were in favor, including 87% of Democrats and 67% of independents. Among Republicans, less than half were in favor (48%, opposed 51%), but on an eleven-point scale of acceptability, 55% found the proposal at least “tolerable” (5-10).

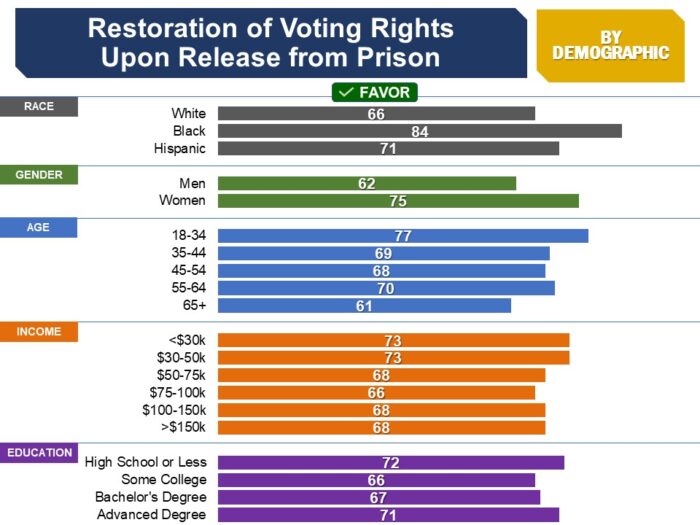

Asked for their final recommendation, a majority of nearly seven in ten (69%) were in favor, including 87% of Democrats and 67% of independents. Among Republicans, less than half were in favor (48%, opposed 51%), but on an eleven-point scale of acceptability, 55% found the proposal at least “tolerable” (5-10). Demographics

Demographics Related Standard Polls

Related Standard Polls