Authorization for Use of Force / Arms Sales

The question of when the United States should use military force is a profound question. There has been a long-running debate about the role of Congress and the President when it comes to making these decisions. The constitution gives Congress the power to fund the military and declare war, and declares the President as the Commander in Chief of the military.

However there are ambiguities about which branch of government has the power in a number of specific situations related to the use of force and the transfer of arms to another country. Currently there are a number of pieces of Congressional legislation that seek to give Congress greater authority.

National Sample: 2,702 registered voters

Margin of Error: +/- 1.9%

Fielded: January 27 - February 28, 2022

- Questionnaire with Frequencies

- Americans on War Powers, AUMFs and Arms Sales: Full Report

- Policymaking Simulation

The survey covered major provisions from the 117th Congress:

- National Security Powers Act of 2021 (S. 2391) by Sen. Murphy (D)

- National Security Reforms and Accountability Act by Rep. James McGovern

- War Powers Act Enforcement Act (H.R. 2108) by Rep. Sherman (D)

- H.R. 255 by Rep. Lee (D)

Proposals with bipartisan support discussed below include:

- Automatically cutting off funding to military operations initiated by the President, outside the framework of a declaration of war, after 60 days, unless Congress votes in favor of continuing it

- Terminating the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force

- Requiring that all arms sales be approved by a majority in Congress

For each proposal, respondents evaluated arguments for and against, rated the proposal on an eleven-point scale of acceptability (with 5 being “just tolerable”), and then made their final recommendation.

|

WAR POWERS ACT |

|

In order to give Congress more control over military operations initiated by a President, Members of Congress have introduced a proposal that would ‘flip the script’ by requiring a simple majority of Congress be required to continue a military operation, rather than the current system which requires a veto-proof majority (two-thirds). This proposal is based on:

Respondents were first introduced to context of the debate over the roles of Congress and the President regarding war powers, as follows: The Constitution gives both Congress and the President a role in the use of military force:

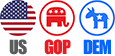

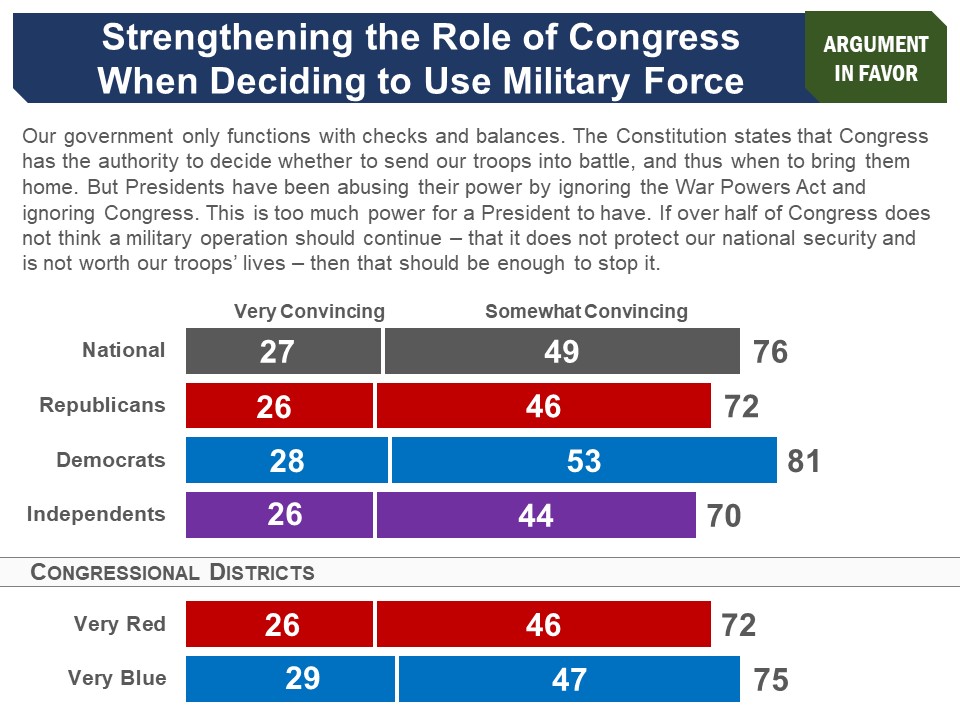

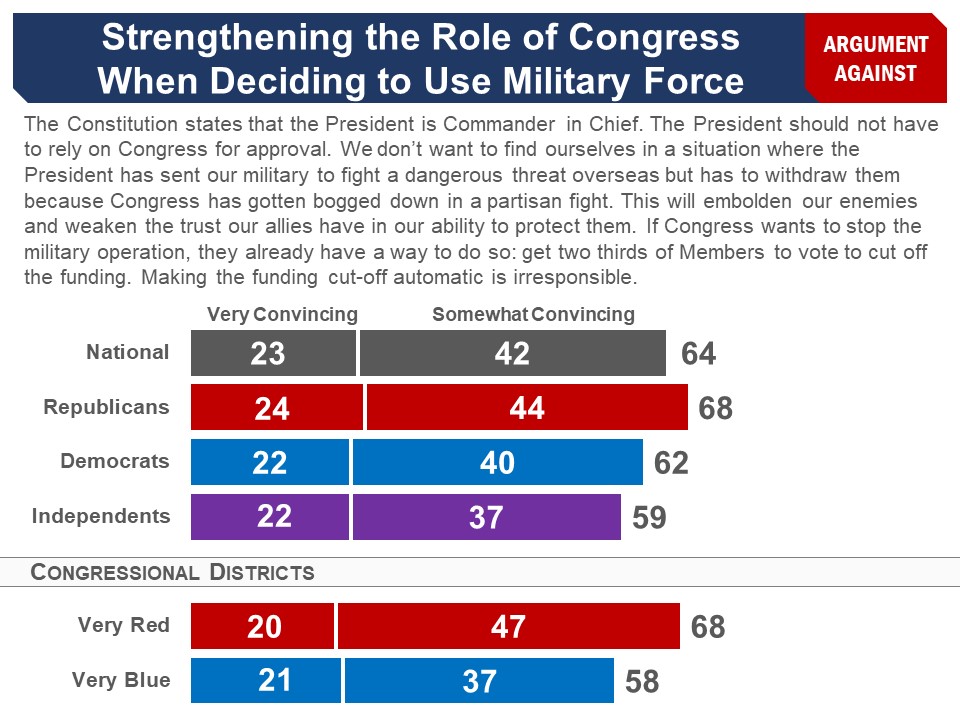

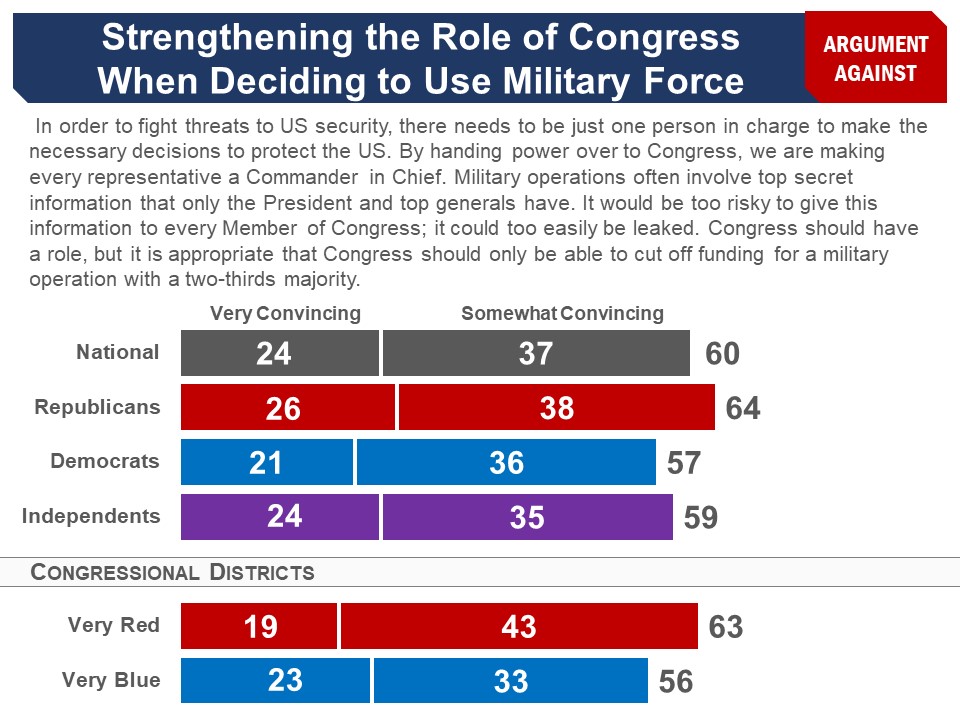

A less clear area is when the President might use military force outside of the framework of a declaration of war. To answer this question, in 1973 Congress passed the War Powers Act. It states that the President may at times use military force without first getting Congressional approval. But if Congress does not vote in favor of continuing the action within 60 days, the President must stop the military action and withdraw the forces. Nonetheless, all Presidents since then have taken the position that, though they may ask Congress for approval, because the President is the Commander in Chief, they do not need Congressional approval to use military force. They were informed that Presidents Reagan, Clinton and Obama had violated the War Powers Acts, and that: In each case, Congress had the option of taking an action to cut off funding for the military operation. However, if Congress were to do that, the President could veto such an action. Then it would require two thirds of the votes in both houses of Congress to override that veto. This is politically difficult to achieve. They were then provided the specific proposal: Currently, there is a proposal that would make it more possible for Congress to stop a President’s military operation. Rather than Congress having to vote to stop a military operation--and possibly be vetoed--the military operation could only continue after 60 days if a majority in Congress were to vote in favor. If Congress does not vote to continue the operation within the 60 days, funding will be automatically cut off. That way the President could not veto this cut-off. (This would not apply to military actions in response to a direct attack on the US or its military.) All of the pro and con arguments were found convincing by bipartisan majorities; but the pro arguments were found convincing by about ten percentage points more people than the cons. The first pro argument exclaimed that our government only functions on checks and balances, and that right now, they are largely absent when it comes to war powers. Seventy-six percent found this convincing (GOP 72%, Dem 81%, Ind 70%). The first con argument rebutted this idea by stating that the Constitution clearly gives the President, as Commander in Chief, full power over military activities. Sixty-four percent found this convincing (GOP 68%, Dem 62%, Ind 59%). The second pro emphasized that use of the military has too many consequences for our foreign policy to be left in the hands of one person, and was found convincing by 71% (GOP 66%, Dem 77%, Ind 68%). The con countered by proclaiming that having just one person in charge is necessary to take quick, decisive action to protect US security, and was found convincing by 60% (GOP 64%, Dem 57%, Ind 59%).

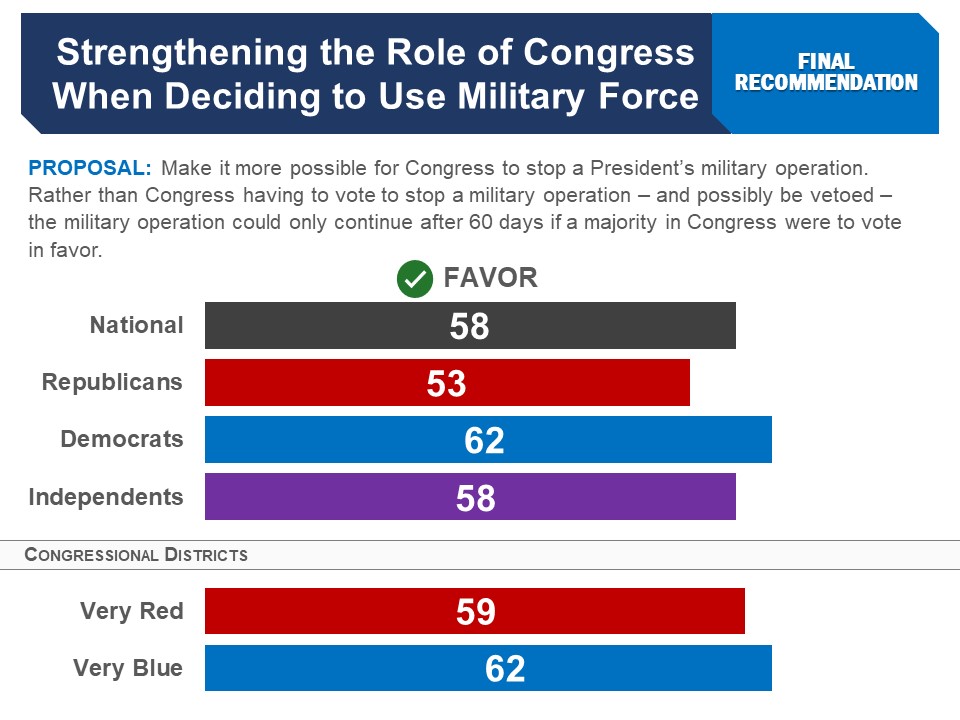

In the end, a bipartisan 58% favored the proposal, including 53% of Republicans, 62% of Democrats and 58% of independents. An analysis of voters by congressional district type, broken out using Cook’s PVI ratings, shows that majorities in all types of districts are in favor, from very red (59%) to very blue (62%). |

|

AUTHORIZATION FOR USE OF MILITARY FORCE |

|

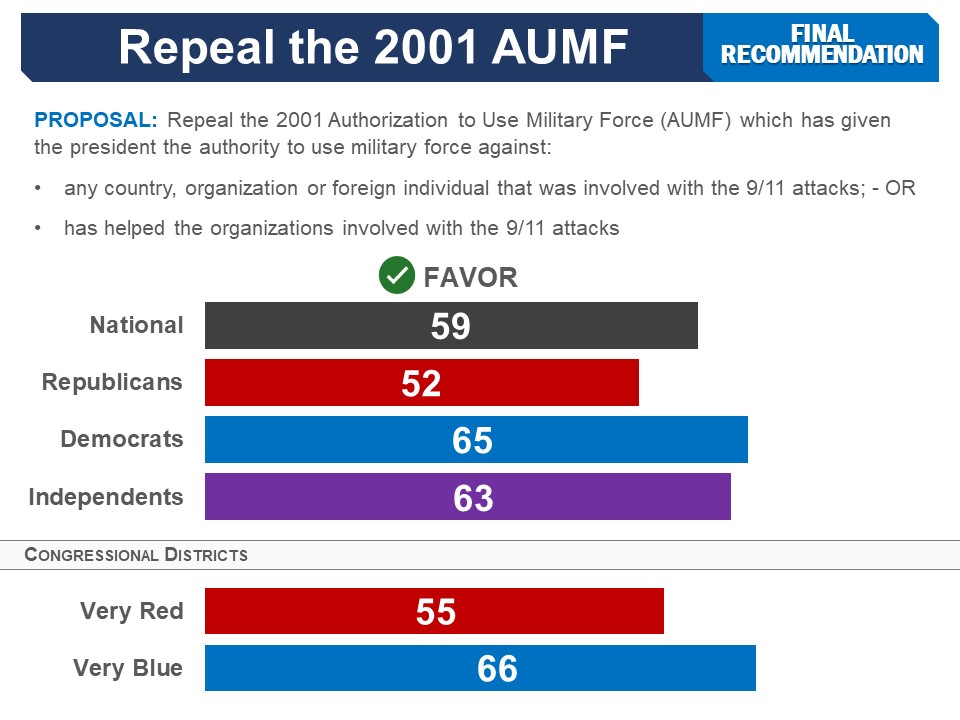

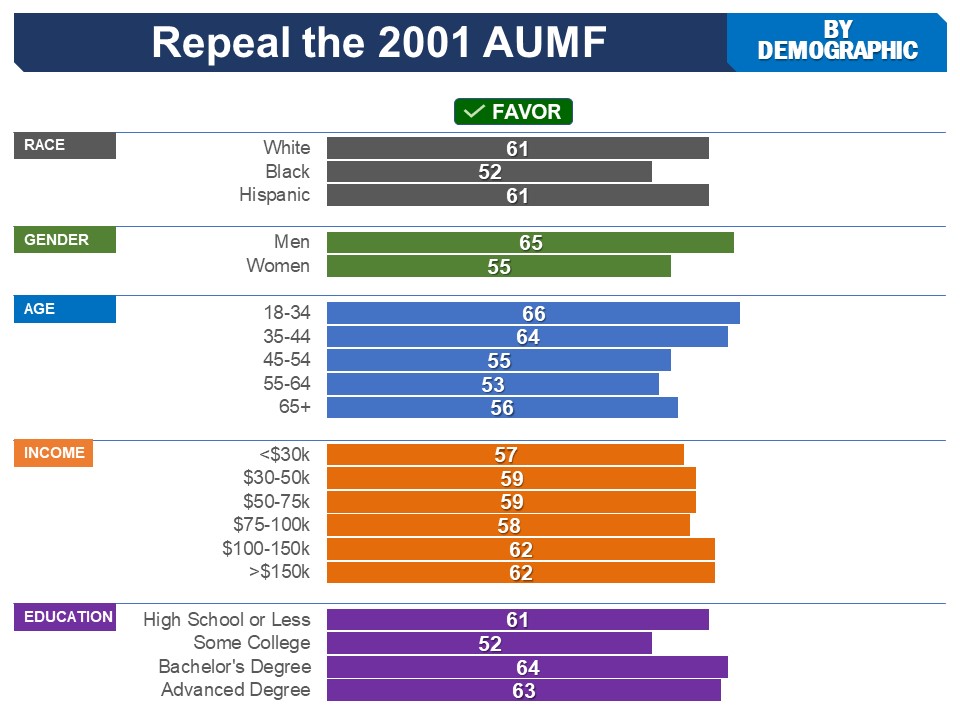

The proposal to repeal the 2001 AUMF, which was passed after the September 11th attacks to give the President the ability to use military force against those involved, was based on:

Respondents were introduced to the context of the proposal as follows: As you may recall, shortly after the 9/11 attacks Congress passed a resolution that gave the president (who was then George W. Bush) the authority to use military force against:

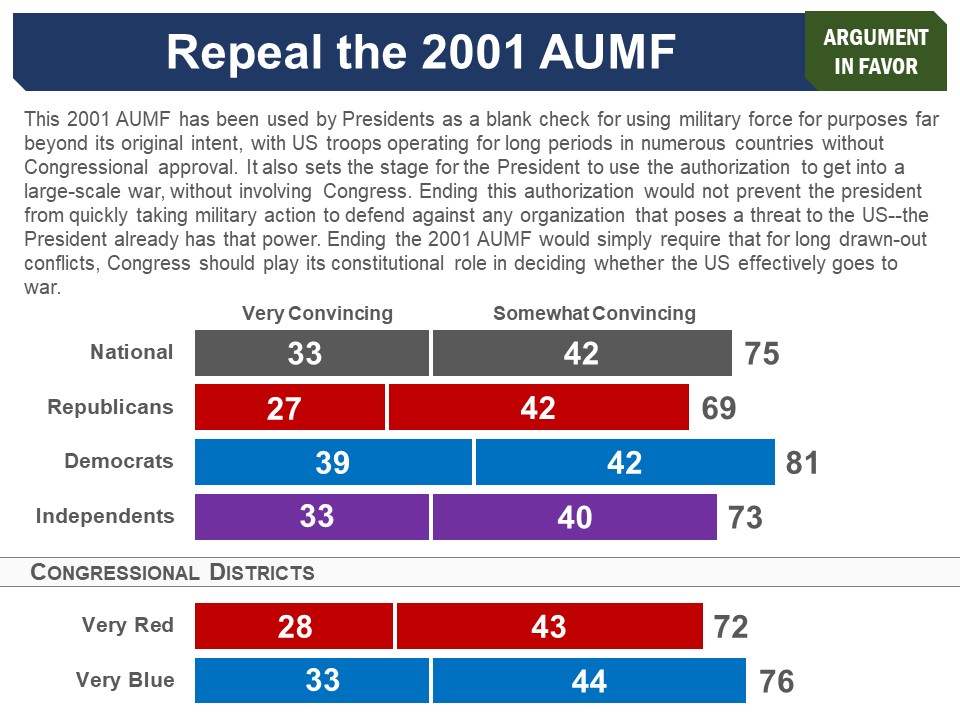

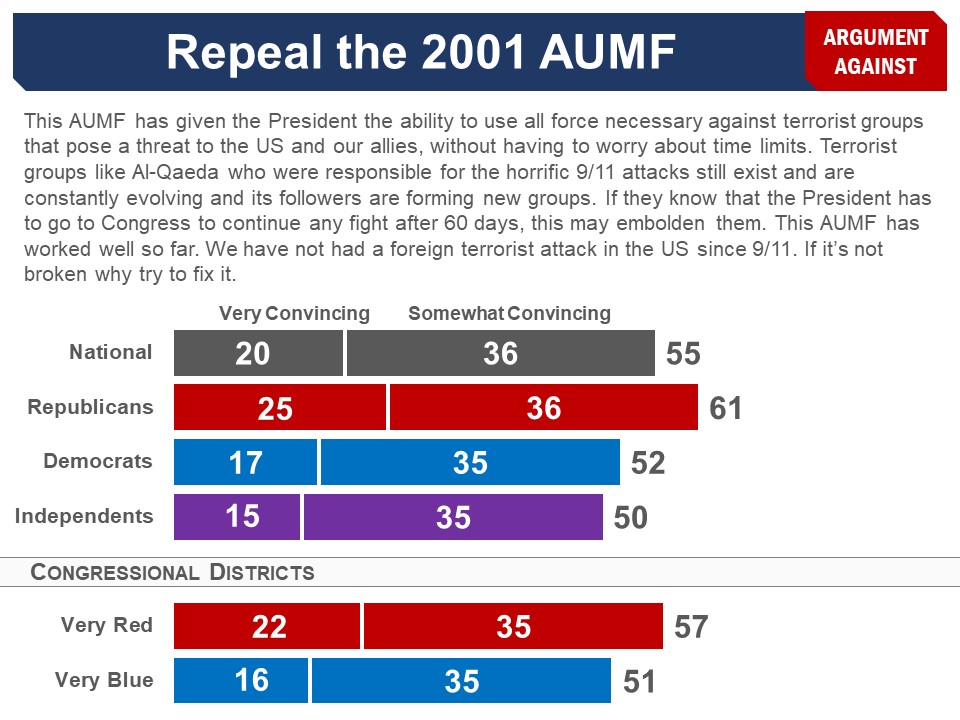

What is controversial is that over the last two decades the 2001 AUMF has been repeatedly used as the legal basis for using military force against organizations that were not involved with 9/11, but have similar beliefs and readiness to use terrorist methods. Since it was passed, the 2001 AUMF has been used by Presidents Bush, Obama, Trump and Biden as the legal basis for dozens of military operations against various organizations in various countries around the world. These include extended operations (longer than 60 days) in Syria, Somalia, Yemen, Libya, and Iraq. The proposal was then presented: A proposal has been put forward to repeal the 2001 AUMF. As discussed above, the President would still have the power to use military force to defend against organizations deemed an imminent threat. But to have an operation that would last longer than 60 days the President would need to get a new AUMF from Congress. Both pro and con arguments were found convincing by bipartisan majorities. The pro argument proclaimed that the 2001 AUMF has been a “blank check” for warfare and has been used beyond its original intent. Three-quarters found this convincing (GOP 69%, Dem 81%, Ind 73%). The con argument declared that it has been necessary to defend the US against terrorist forces, and was found convincing by 55%, including 61% of Republicans and a bare majority of Democrats (52%). Independents were divided.

A large bipartisan majority favored President Obama asking for Congressional approval to continue using force against ISIS, authority which was later justified using the 2001 AUMF:

Status of Legislation |

|

ARMS SALES |

|

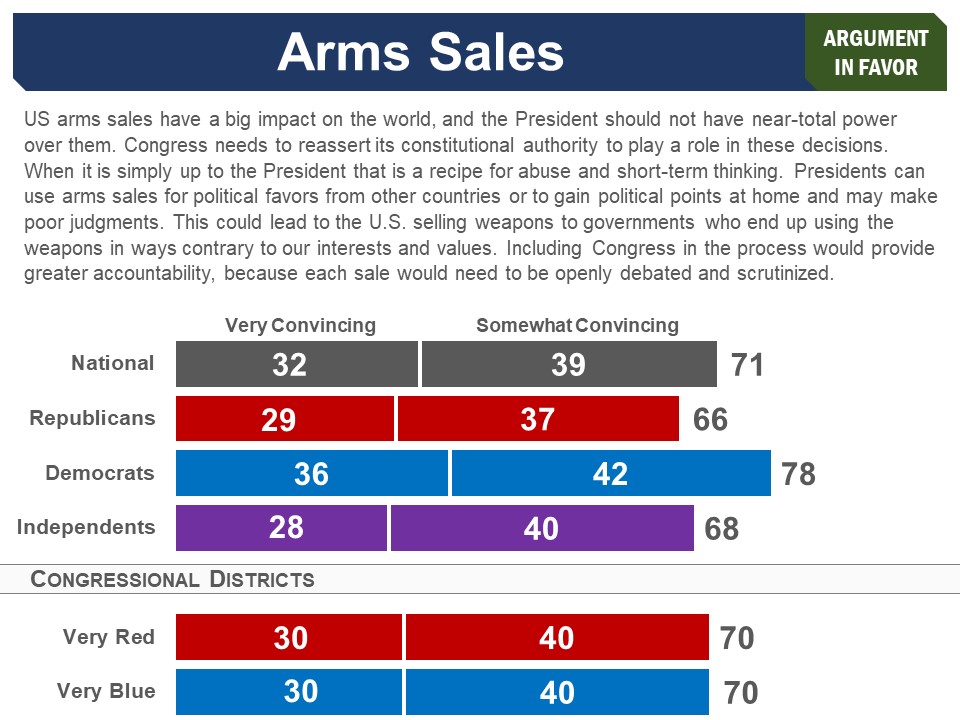

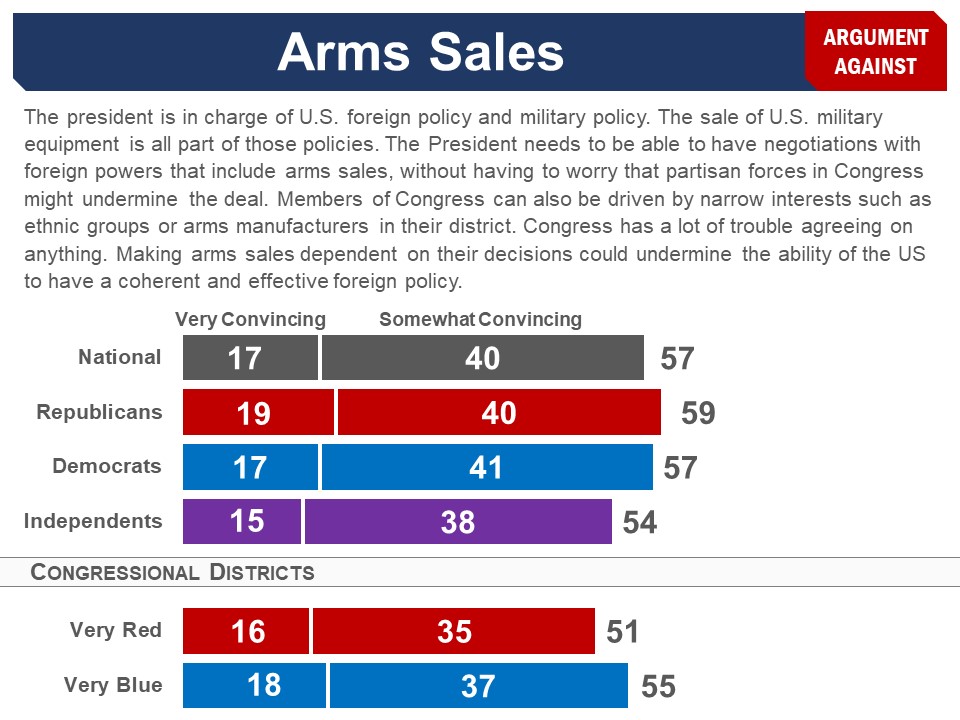

In order to give Congress more control over arms sales, which need approval by the President, Members of Congress have introduced a proposal that would ‘flip the script’ by requiring a simple majority of Congress be required to approve a large arms sale, rather than the current system which requires a veto-proof majority (two-thirds) to stop one. This proposal is based on:

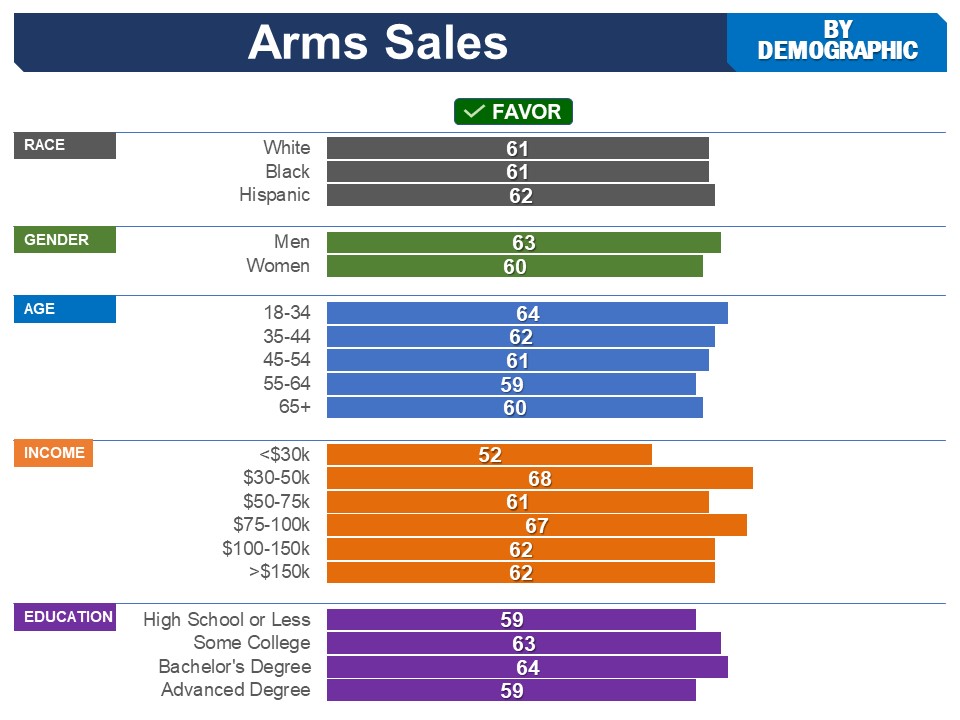

Respondents were introduced to context of the debate about the roles of Congress and the President regarding arms sales, as follows: Now let’s turn to another issue: the sale of US-made military equipment -- such as planes, missiles, tanks and military computer technologies -- to foreign governments. As you may know, Congress passed a law in 1976 that gave the President the power to approve all such arms sales. This law states that Congress can disapprove of a sale of military equipment over $14 million dollars. But the President can veto such an action. Then it would require a two thirds vote in both houses of Congress to override the veto. In fact, Congress has never succeeded in stopping an arms sale. The proposal was then presented: Currently, there is a proposal that would make it more possible for Congress to stop an arms sale over $14 million. Rather than Congress having the power to vote to stop an arms sale--and possibly be vetoed--arms sales could only occur if a majority in Congress were to vote in favor of the sale. This would mean that Congress could stop a sale with 51% of votes in both houses of Congress, while currently it could require 2/3s of both houses. Both pro and con arguments were found convincing by a bipartisan majority. The pro argument voiced the concern that, since arms sales have such a big impact on foreign policy, they should not be left up to one person. Seventy-one percent found this convincing (GOP 66%, Dem 78%, Ind 68%). The con stressed that the President should have more power than Congress over foreign policy and any military-related activities. Fifty-seven percent found this convincing, with little partisan difference (GOP 59%, Dem 57%, Ind 54%). |