Medicare

The Medicare Board of Trustees has reported for some years that, as the Baby Boom generation retires, the Medicare Trust Fund is being depleted as benefits have been superseding revenues. This is known as the Medicare “shortfall.” The most recent report concluded that if no changes are made to Medicare revenues and/or benefits and other costs, the Trust Fund will be depleted by 2031 and benefit levels will have to be scaled back.

However, there has only been one reform made to Medicare to address this shortfall: giving Medicare the ability to negotiate prices for certain drugs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC) have put forward options for addressing this shortfall.

- National Sample: 7,959

- Margin of Error: +/- 1.1%

- Fielded: August 24 - October 10, 2016

There were also an oversample of 251 respondents in Maryland, Oklahoma and Virginia. These data can be found in the questionnaire.

The Medicare program was briefly introduced and explained as “the federal program that was established in 1965 to provide health care for Americans age 65 and older.” Medicare’s shortfall was then explained as follows:

When the Medicare Trustees have looked at Medicare’s expenses for the next 25 years, they find that there is a shortfall. This shortfall is the gap between Medicare’s commitments to retirees and the amount of projected revenue. Over the next 25 years, this shortfall averages $230 billion a year. Medicare can cover this long‐term shortfall by either reducing its costs or increasing its revenues, or a combination of both.

Respondents then saw a series of graphs and charts explaining some of the shortfall’s causes:

- The projected increase in the absolute number of Americans over 65

- The growth in Americans’ average life expectancy

- The rise in overall healthcare costs

- The falling ratio of workers paying Medicare’s payroll tax to each Medicare recipient

Respondents were then given an overview of Medicare’s costs and services provided, as well revenues from the payroll tax, general revenues and premiums.

Respondents were presented 11 reform options. Four of them included two to three tiered sub‐options. Thus, a total of 16 options were considered. Each option was scored in terms of the percentage of the shortfall it would cover. The reform options fell under four broad categories:

- Reducing Medicare’s Net Payments for Benefits

- Reducing Payments to Providers

- Increasing Revenues

- Controlling Costs in Other Ways

These options were previously scored by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), except for one scored by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission or MEDPAC, another independent agency that advises Congress.

For each reform option, respondents received a briefing and evaluated pro and con arguments. They then evaluated each option on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being completely unacceptable, 10 being completely acceptable and 5 being just tolerable.

After considering each option separately, all of the options were presented together in a single spreadsheet, with the percentage of the shortfall each would cover. Respondents were then asked to make their final recommendations by selecting among the options the ones they would recommend to their member of Congress. An interactive feature gave respondents immediate feedback on the impact of their choices on the shortfall.

Because not all of the options for addressing Medicare were presented in the process, and covering the shortfall with the available options was challenging, respondents were not urged to try to cover the full shortfall. They were told that “These are not all the proposals that have been put forward,” but that they “represent a major starting point for dealing with the problem.”

Proposals with bipartisan support discussed below include:

- Encouraging the use of generic drugs by lowering costs for generic drugs and raising them for name brand drugs

- Requiring drug companies to accept less money for drugs that go to people with modest incomes

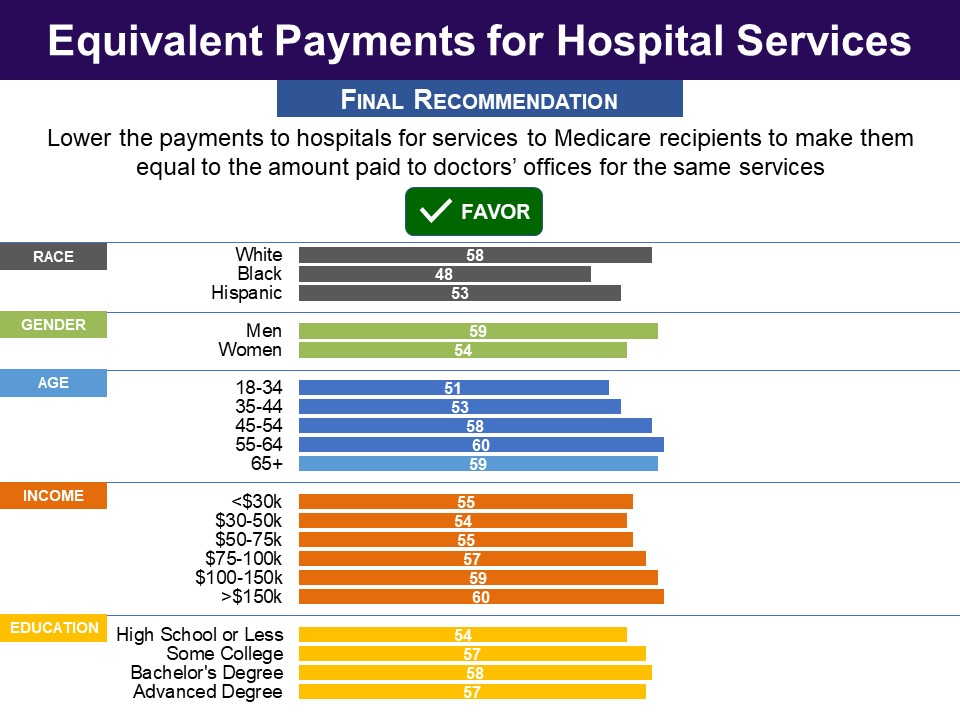

- Reducing payments to hospitals to equalize them with payments made for the same services when conducted in doctors’ offices

- Raising the Medicare payroll tax

- Increasing Medicare premiums that cover outpatient services for those with incomes over $85,000

- Increasing standard premiums

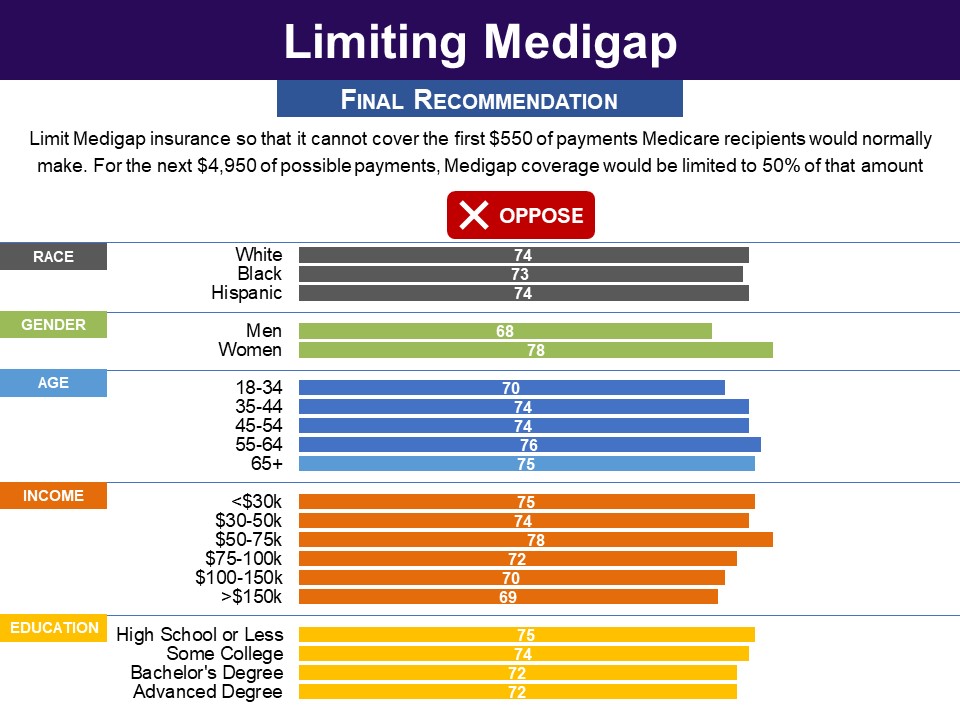

- Limiting the amount of Medigap coverage that seniors can buy from private companies to cover the payments that Medicare does not cover

- Limiting payments from malpractice lawsuits

Proposals that did not have bipartisan support include:

- Increasing outpatient deductibles, compensated by lowering deductibles for hospitalizations and capping all out-of-pocket costs

- Raising the age of eligibility from 65 to 67

- Lowering the subsidy that Medicare provides to teaching hospitals for training doctors

Of all the reform options, seven were favored by bipartisan majorities, which together would cover 30% of the Medicare shortfall. One more option was endorsed by a majority overall and by one party, with a majority of the other party finding it at least tolerable. With this option included 41.8% of the shortfall would be covered.

An additional proposal for increasing the payroll tax that would cover an additional 22.6% of the shortfall was not favored by the majority but was found tolerable by majorities overall and by both parties, bringing the total coverage to 64.4%.

|

REDUCING PAYMENTS FOR BENEFITS |

|

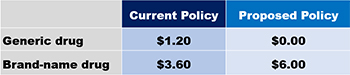

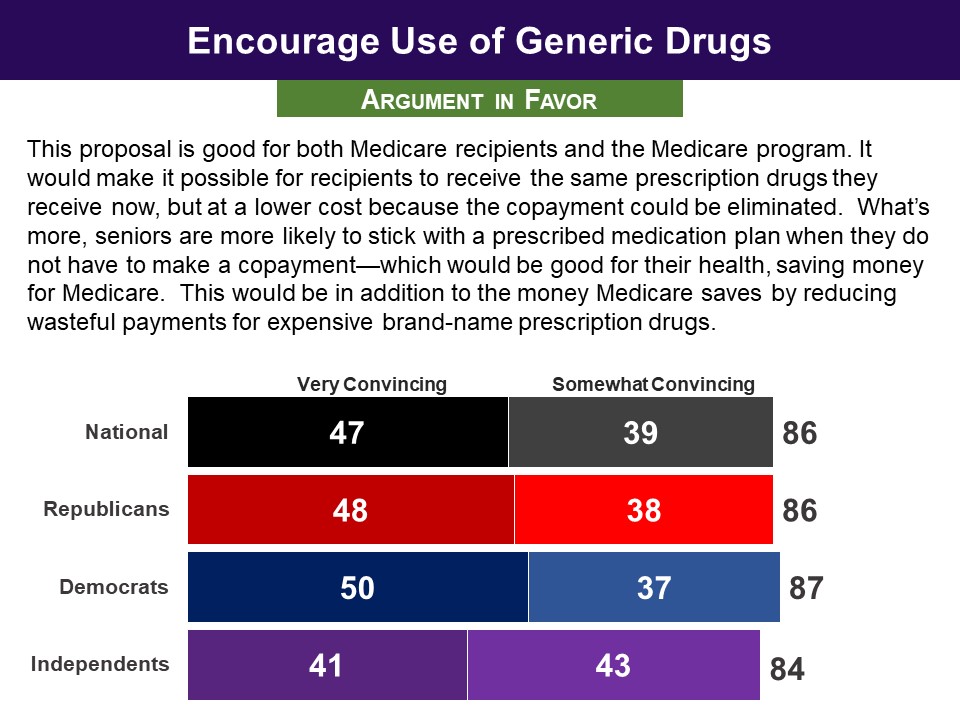

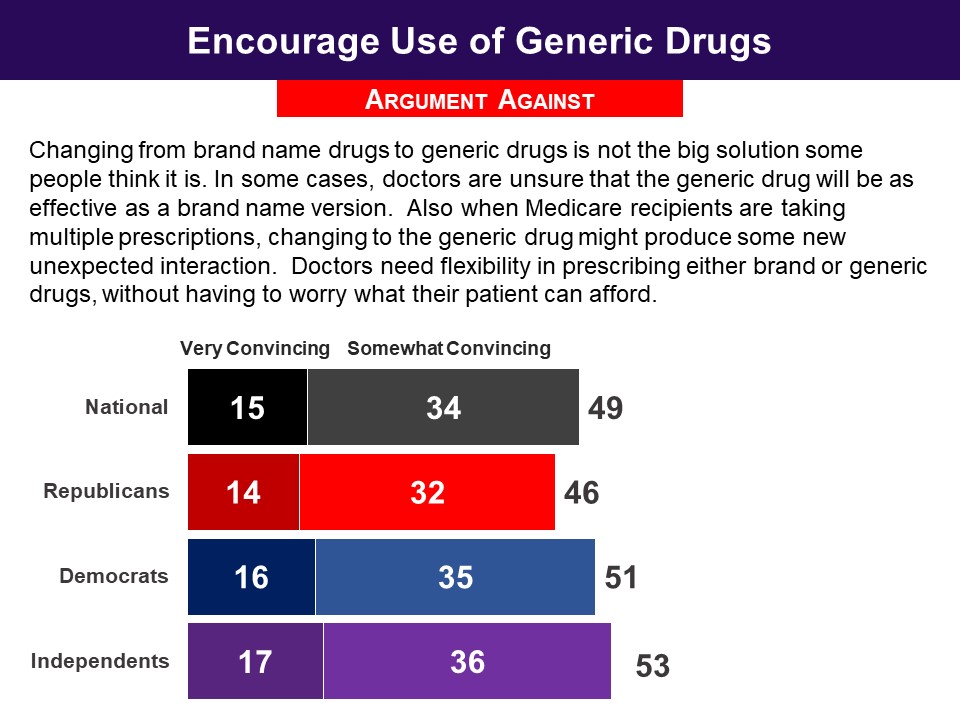

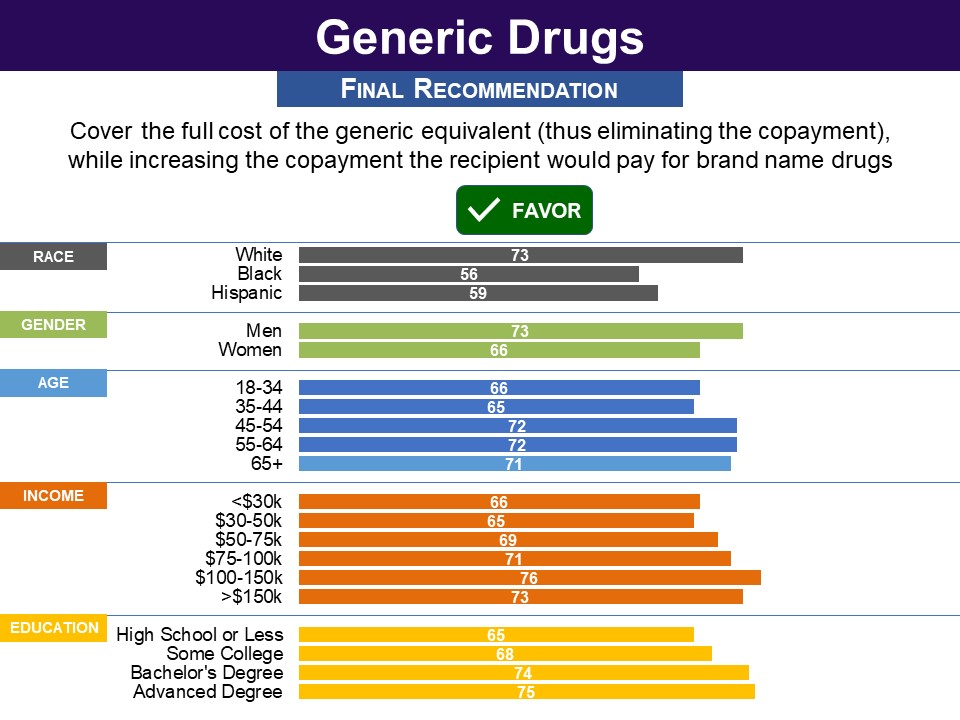

Respondents were presented a proposal for having Medicare cover a smaller portion of the price of brand name drugs while covering the full cost of those drugs’ generic equivalents: (A) proposal for reducing costs is meant to encourage some Medicare recipients to switch from brand name to generic prescription drugs when an equivalent one is available. Medicare would cover the full cost of the generic equivalent (thus eliminating the copayment), while increasing the copayment the recipient would pay for brand name drugs. Here is how a typical copayment for a prescription would change:

This proposal would cover 2% of the shortfall (on average $5 billion a year). The argument favoring the proposal was widely embraced, with 86% finding it convincing, with minimal partisan differences. The argument against the proposal produced a divided response overall. A minority of Republicans found it convincing (46%) and Democrats were divided (51% to 49%). Related Standard Polls

|

|

REDUCING PAYMENTS TO PROVIDERS |

|

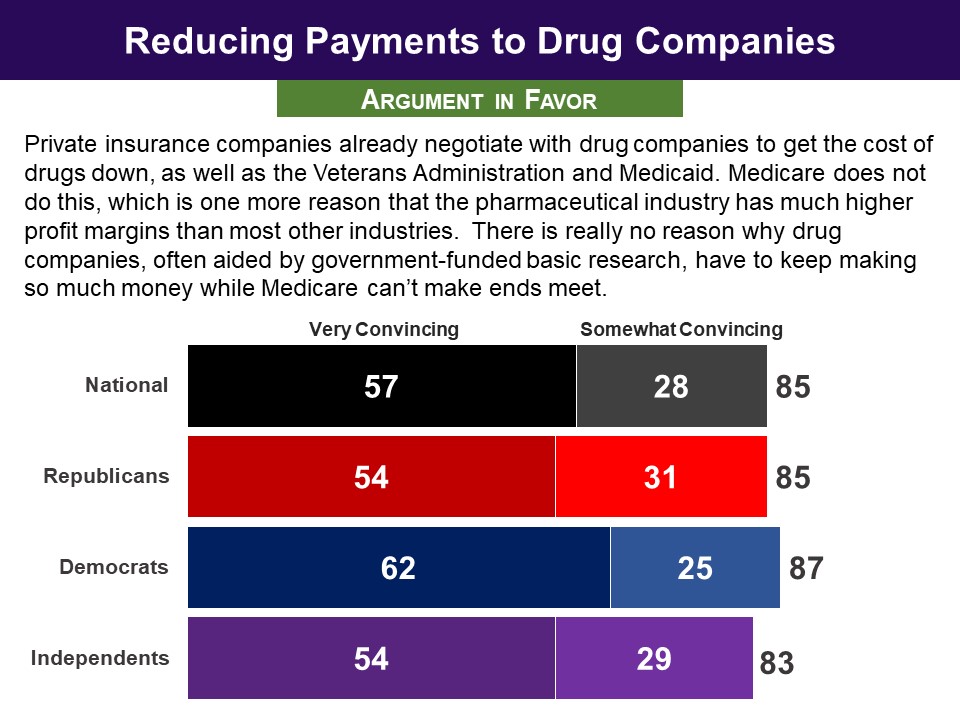

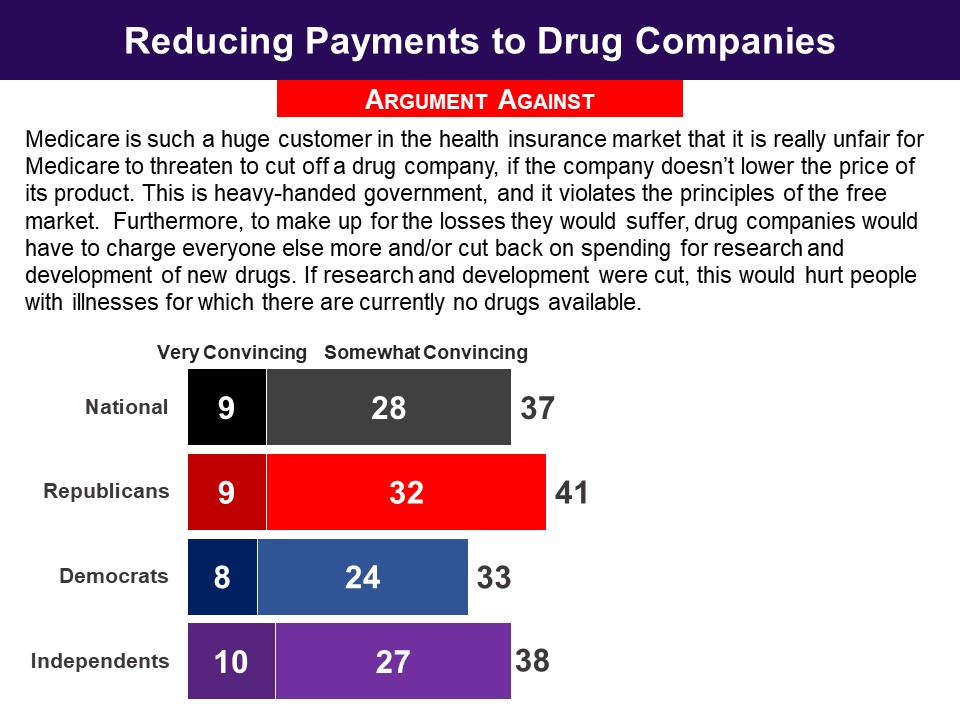

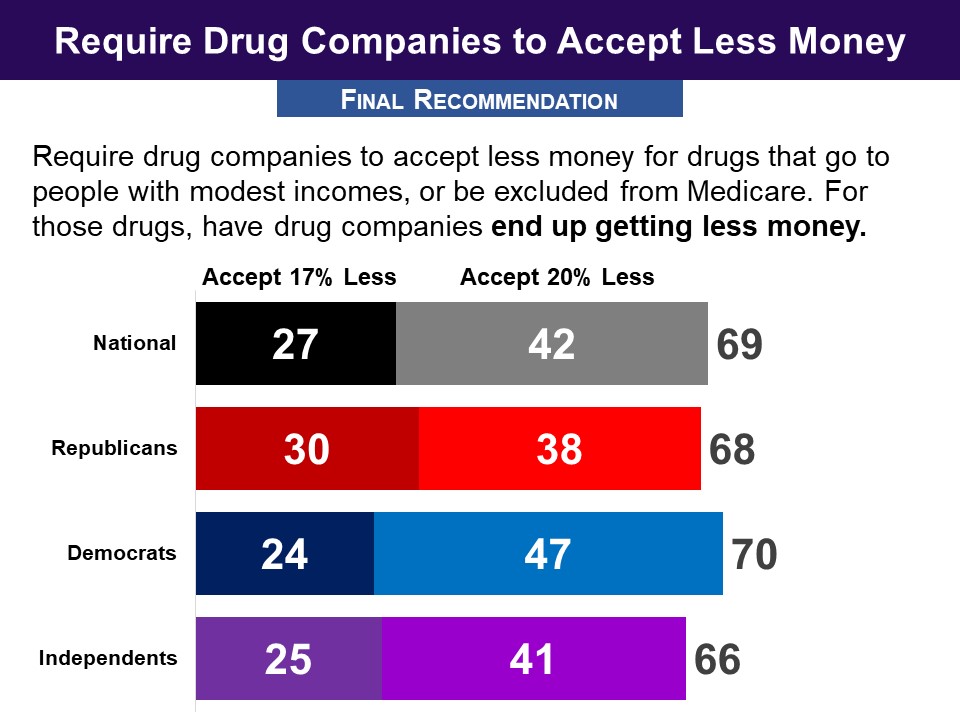

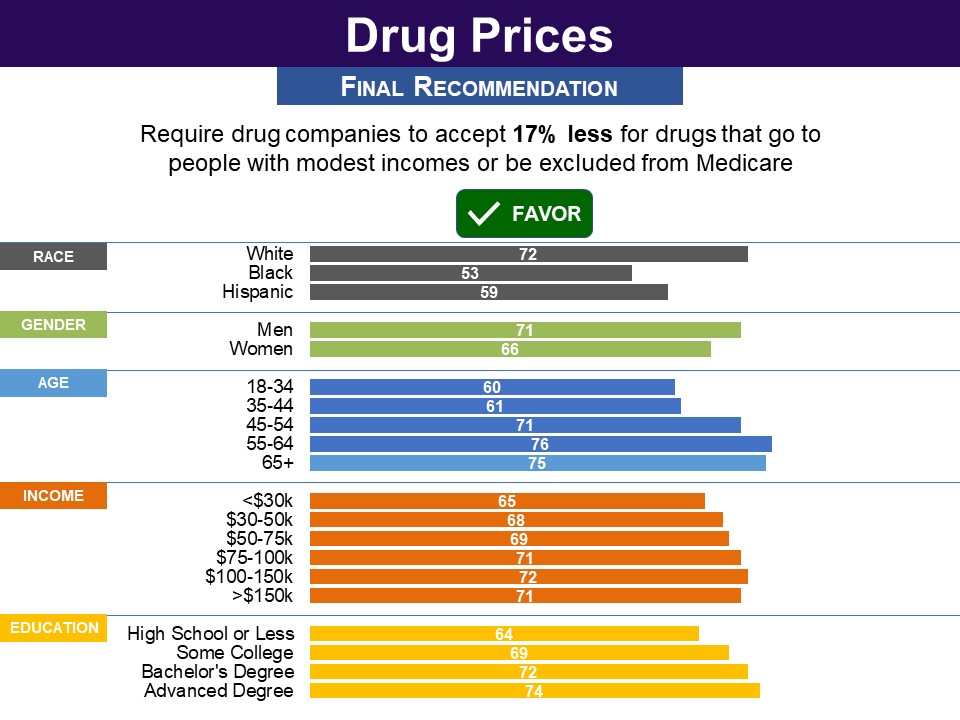

Respondents were presented the following proposal: Drug companies would be required to accept getting less money for the drugs that go to people with modest incomes or they would be excluded from Medicare. One proposal is for drug companies to get 17% less money. This would save Medicare an average of $7.5 billion, or 3% of the shortfall, annually. Another proposal is for drug companies to get 20% less money. This would save Medicare an average of $16.1 billion, or 7% of the shortfall, annually. The argument favoring this proposal was found convincing by a remarkably high 85% (57% very), with minimal partisan differences. The argument countering the proposal was rejected to a striking degree—something unusual in a policy simulation. Only 37% found it convincing. Response Without Undergoing Policymaking Simulation |

|

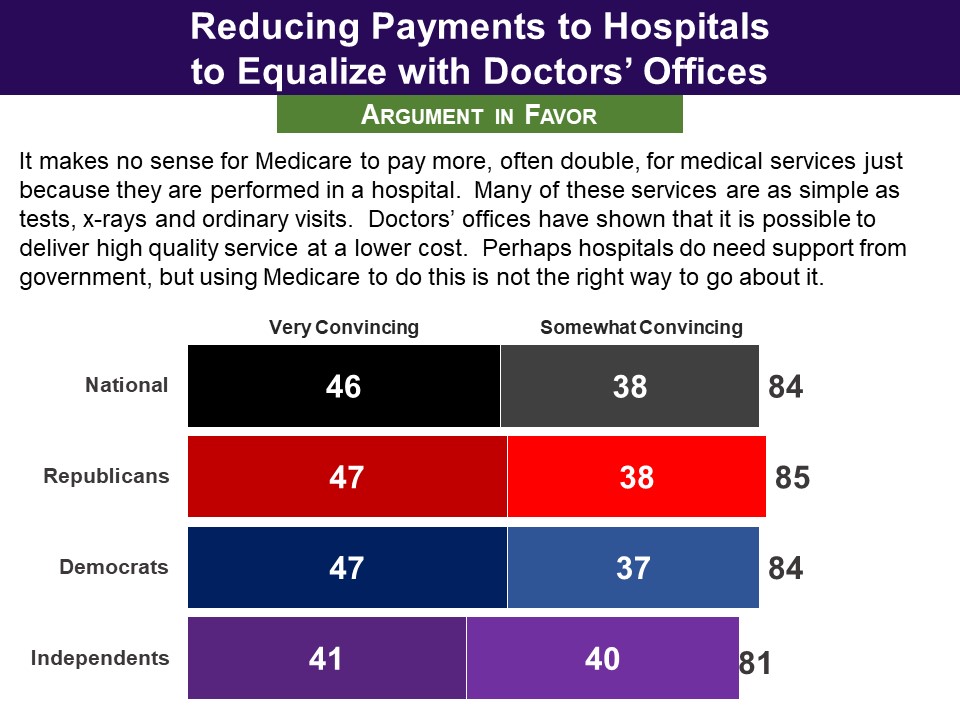

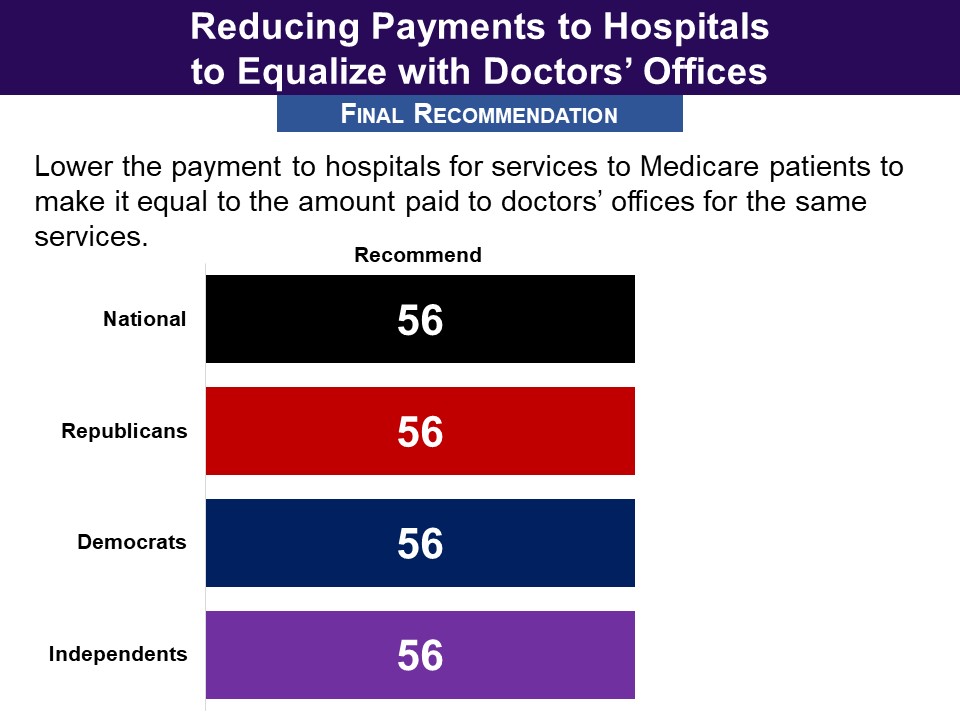

Respondents were presented the following proposal: Another proposal would reduce the amount of money it currently pays to hospitals for some services. Currently, Medicare sometimes reimburses hospitals at higher rates for the exact same services that it reimburses doctors’ offices. This proposal would lower the payment to hospitals for services to Medicare patients to make it equal to the amount paid to doctors’ offices for the same services. This proposal would cover 2% of the shortfall (saving an average of $5 billion annually). The argument in favor did substantially better than the argument against.The pro argument was found convincing by over four in five (84%), with minimal difference between the parties. The con argument did not do very well, with less than half (46%) finding it convincing. |

|

INCREASING REVENUES |

|

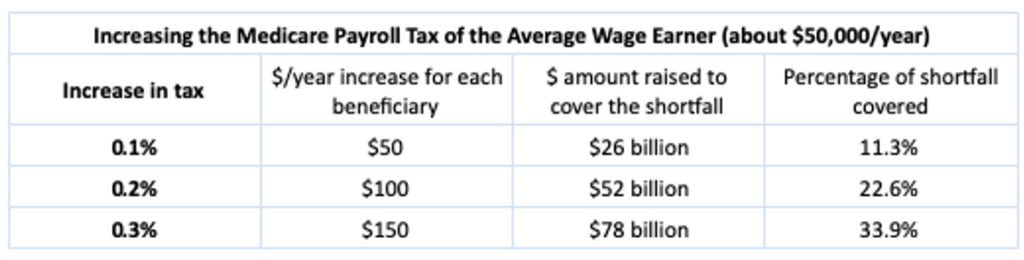

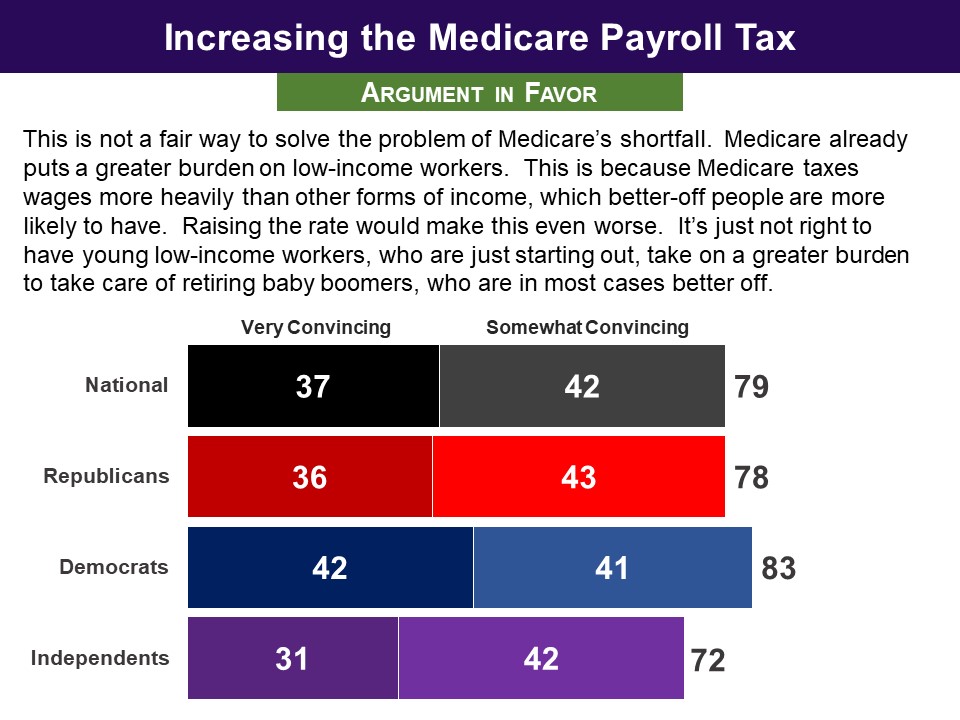

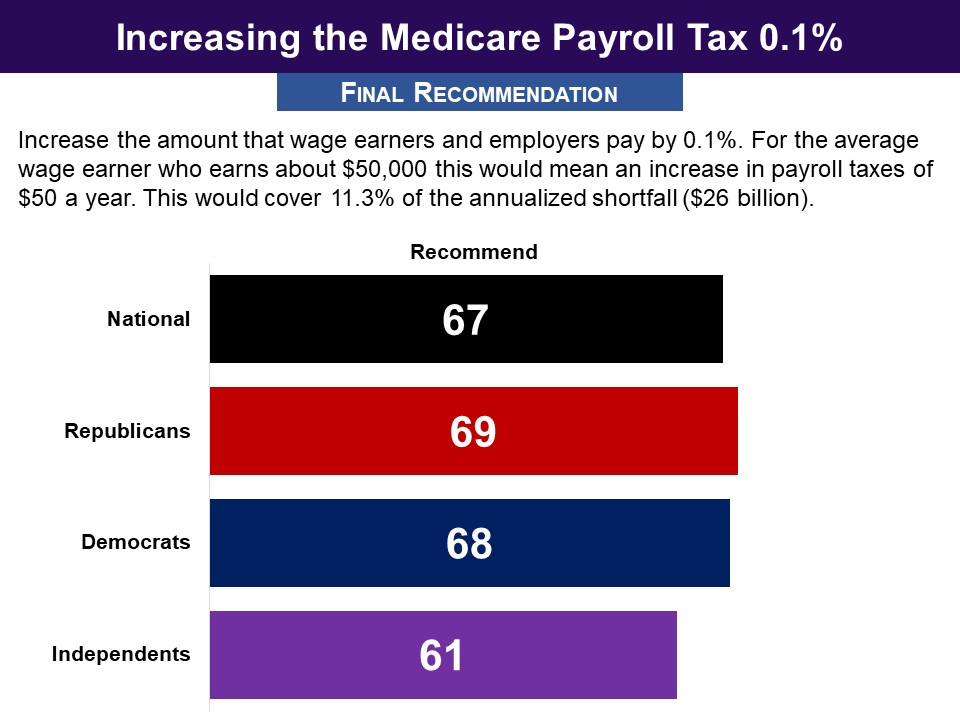

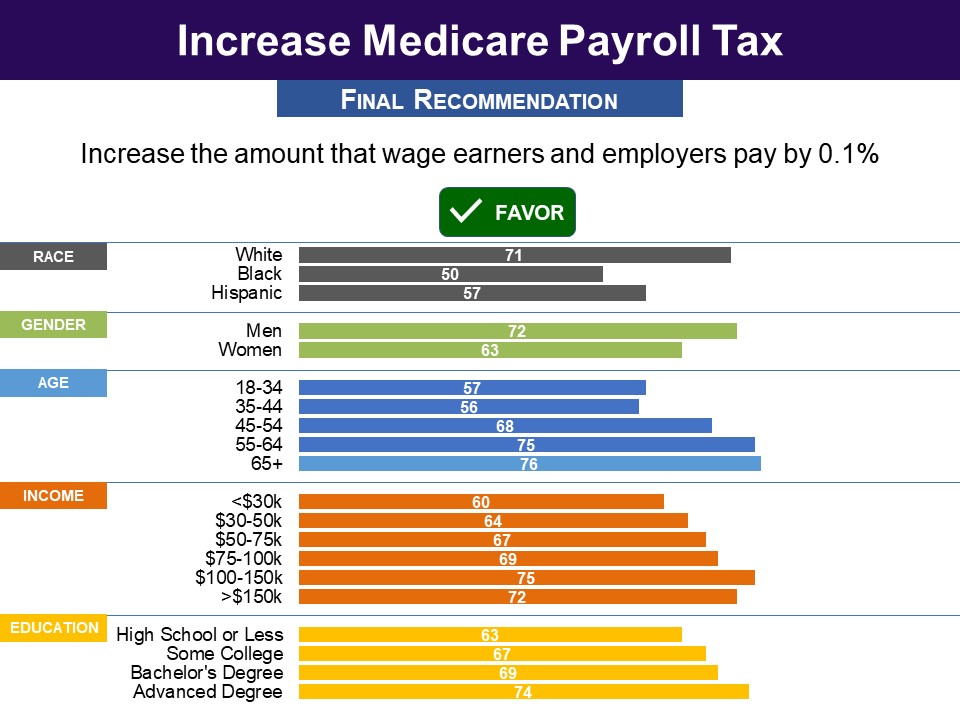

Respondents were presented a proposal to raise revenue: One proposal would be to increase the Medicare payroll tax. Currently, Medicare’s hospital insurance program (Part A) is financed by payroll taxes. All wage earners pay 1.45% of their wages and the employer pays 1.45% of those wages as well. People with high incomes (over $200,000) pay an extra 0.9%, including on investment income. The proposal is to increase the amount that wage earners and employers pay by 0.1%, 0.2%, or 0.3%. For the average wage earner, who earns about $50,000 a year, this would mean an increase in payroll taxes of $50 to $150 a year. The 0.1 percent increase that received majority support would cover 11.3% of the shortfall. The 0.2% increase that was found widely tolerable, would raise that to a 22.6% level of coverage and a 0.3% increase, also found tolerable, would raise it to 33.9% coverage. While the least well‐off would be the most affected by such an increase, 60% of those with incomes below $30,000 a year chose the 0.1 percent increase. At the highest income level (those above $150,000) a larger 72% chose the 0.1 percent increase. However, in no income group did more than half recommend a 0.2 percent increase. Response Without Undergoing Policymaking Simulation Related Standard Polls

|

|

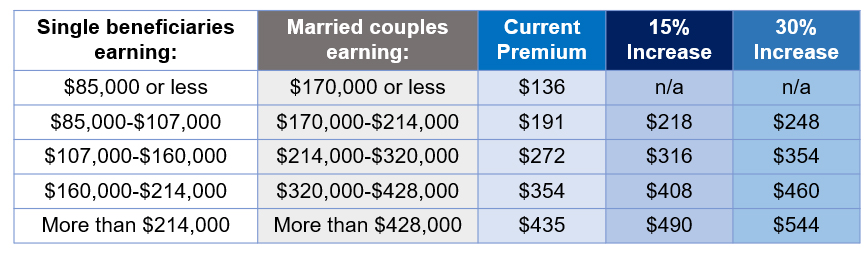

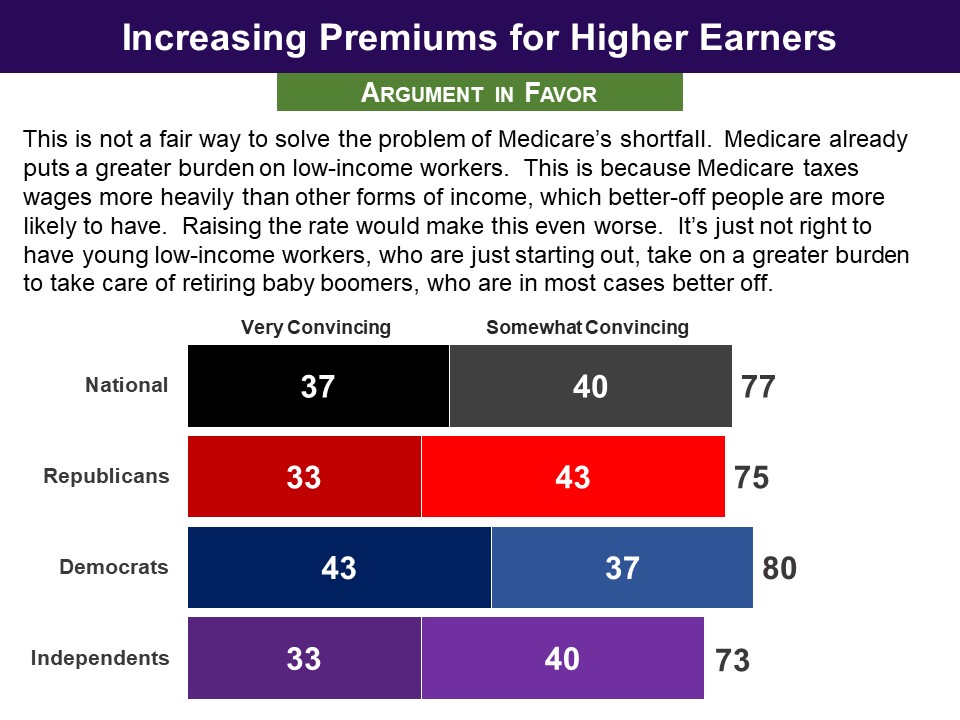

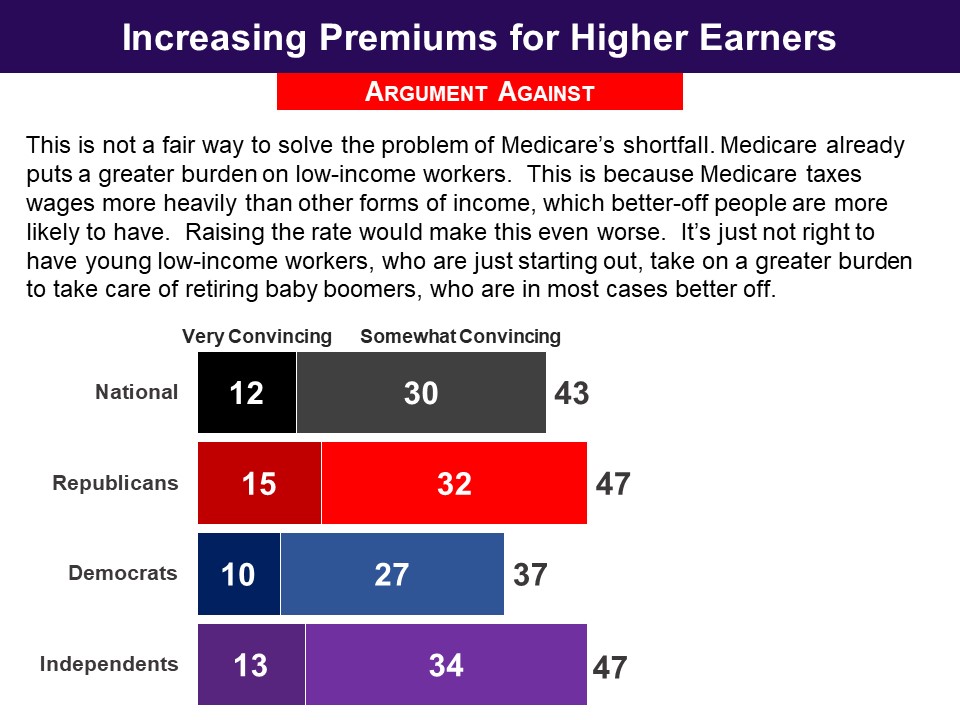

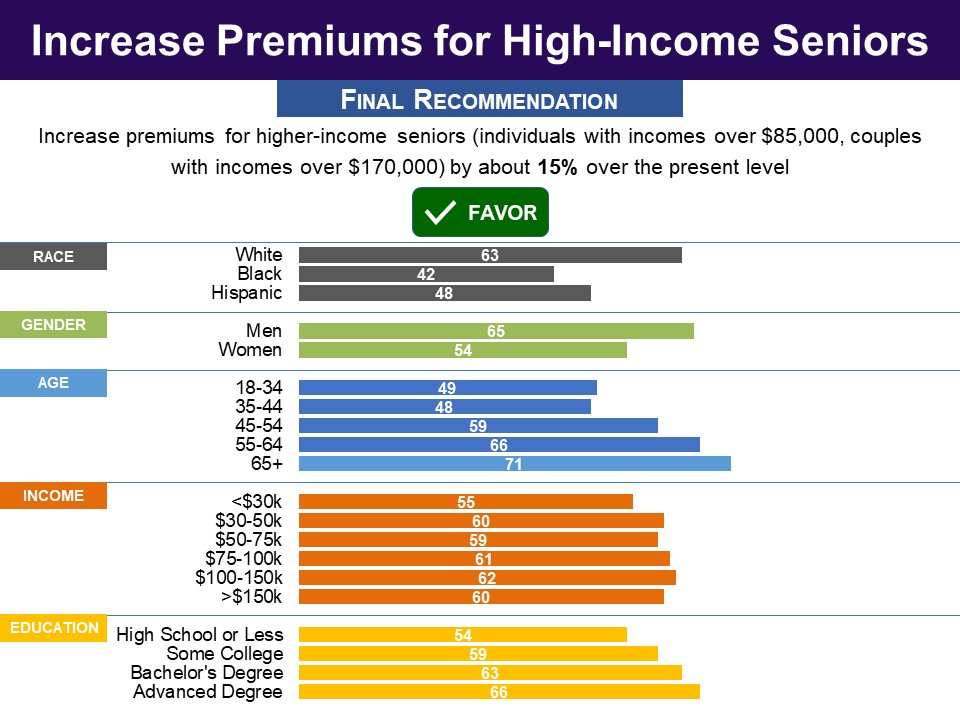

Respondents were presented a proposal to increase revenues: Another proposal is to increase the premiums paid by Medicare recipients to cover outpatient services. While the Medicare payroll tax that all workers pay covers Medicare’s hospital insurance program, it does not cover any outpatient services. Right now it costs Medicare about $544 a month to cover outpatient services (including drugs). About one quarter of the costs are paid for by premiums paid by Medicare recipients and the rest is paid by the Federal government from year-to-year general revenues (such as income taxes). Thus most Medicare recipients pay a standard premium of about $136 a month. Recipients with higher incomes-- over $85,000 for single people, $170,000 for married couples--already pay more than the standard premium, depending on their level of income. These upper-income recipients include about the top 6% of all recipients. One version of the proposal for increasing premiums would increase premiums for these higher-income seniors by 15% over the present level. Another version of the proposal would raise these premiums by 30%. They were then presented a table showing, “how premium costs would change for different income levels if such increases were to be adopted.” Respondents evaluated arguments for and against the proposal. The argument in favor did substantially better than the argument against, which was not found convincing by any majority. The argument in favor of a premium increase was found convincing by over three in four, with a minimal partisan difference. The argument against was found convincing by just 43%. Response Without Undergoing Policymaking Simulation Related Standard Polls

When framed as a means to reduce the federal deficit, a bipartisan majority has favored increasing Medicare premiums on high earners:

|

|

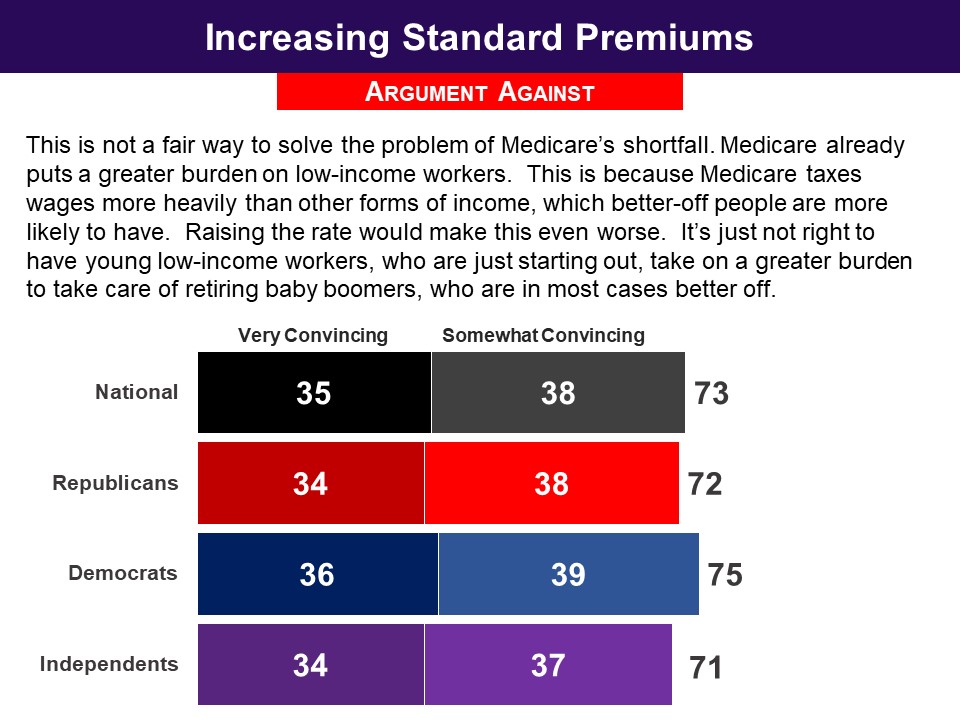

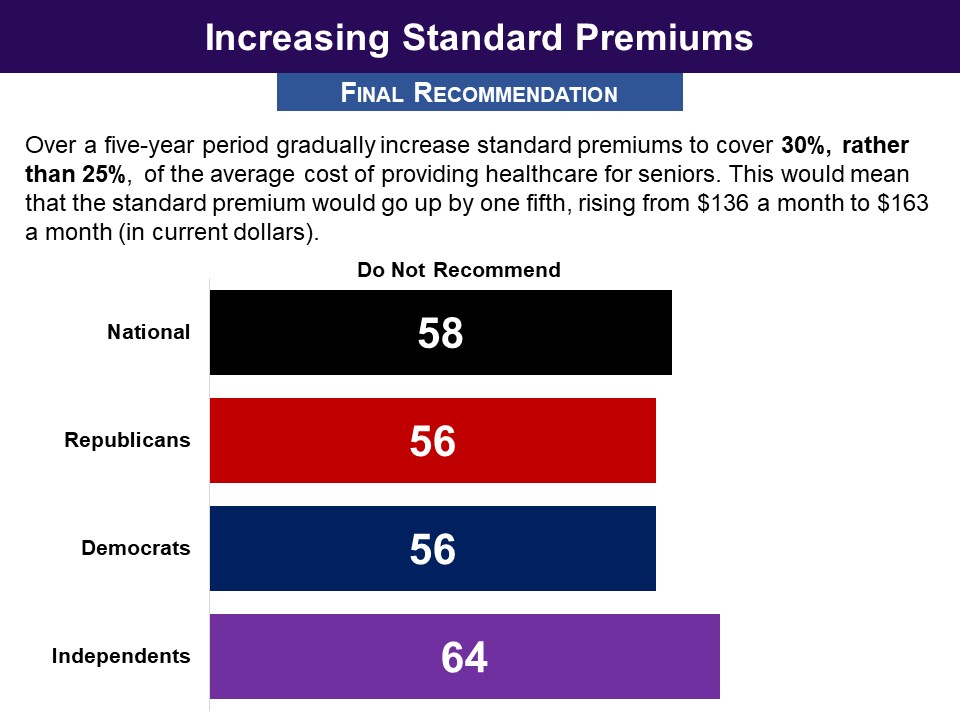

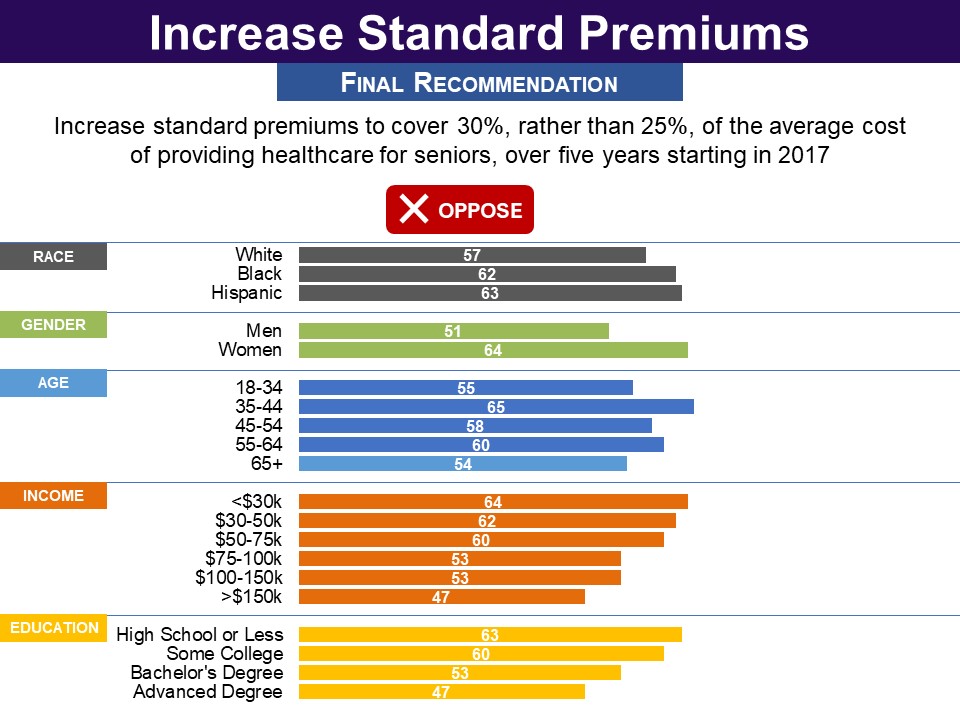

Respondents were presented a proposal to increase revenues: Another proposal for increasing income from Medicare recipients would be to increase standard Medicare premiums—the amount most seniors pay each month. As mentioned, standard premiums cover 25% of the average cost of providing healthcare for a person on Medicare. A version of the proposal would gradually increase standard premiums to cover 30%, rather than 25%, of the average cost of providing healthcare for seniors. The increase would take place over a five-year period beginning in 2017. This would mean that the standard premium would go up by one-fifth, rising from $136 a month to $163 a month (in current dollars). This would cover 16% of the shortfall ($36 billion annually). Another version of the proposal would gradually increase, over five years, standard premiums to cover 35% rather than 25% of the average cost of providing healthcare for seniors. The standard premium would go up by two-fifths, rising from $136 a month to $190 a month (in current dollars). This would cover 32% of the shortfall ($72 billion annually). For both versions, the increase would not affect high-income Medicare recipients, who are already paying higher premiums, or low-income recipients who have total resources of less than $13,000 for an individual and income at 150% or less of the poverty line. When they evaluated arguments for and against the proposal to increase standard premiums, both arguments were found convincing by bipartisan majorities, but the argument against did substantially better. The argument in favor was found convincing by a modest majority (54%). The argument against was found convincing by 73%. Asked about a higher rise to 35‐percent coverage of Medicare’s costs, it was found unacceptable (0-4) by 58% overall (Republicans 59%, Democrats 57%). Related Standard Polls

When framed as a means to reduce the federal deficit, even larger bipartisan majorities have opposed raising Medicare premiums:

|

|

CONTROLLING COSTS IN OTHER WAYS |

|

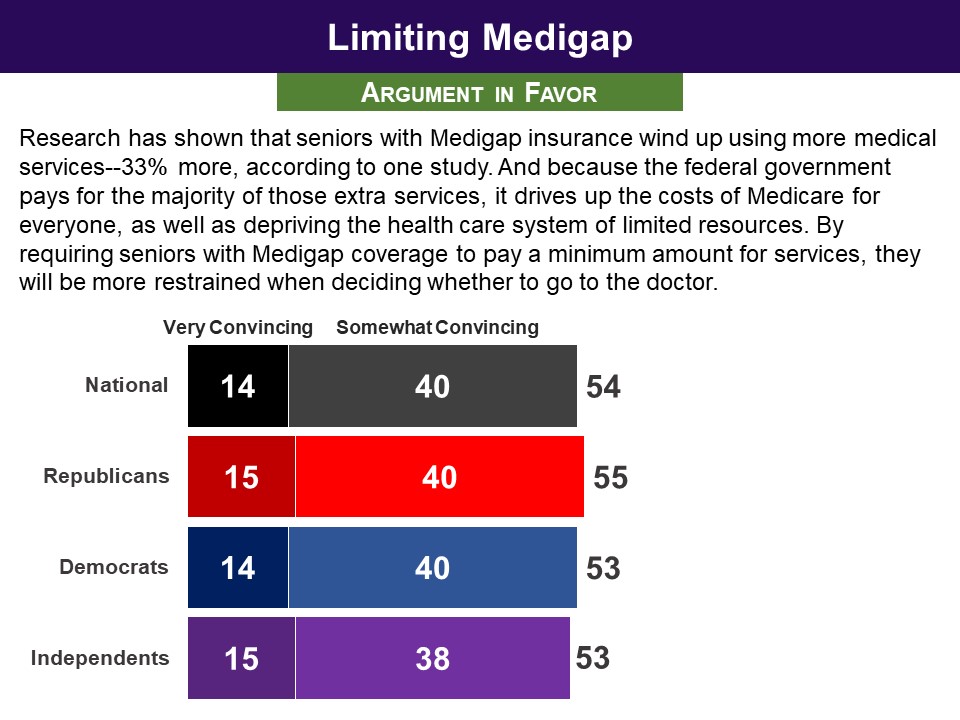

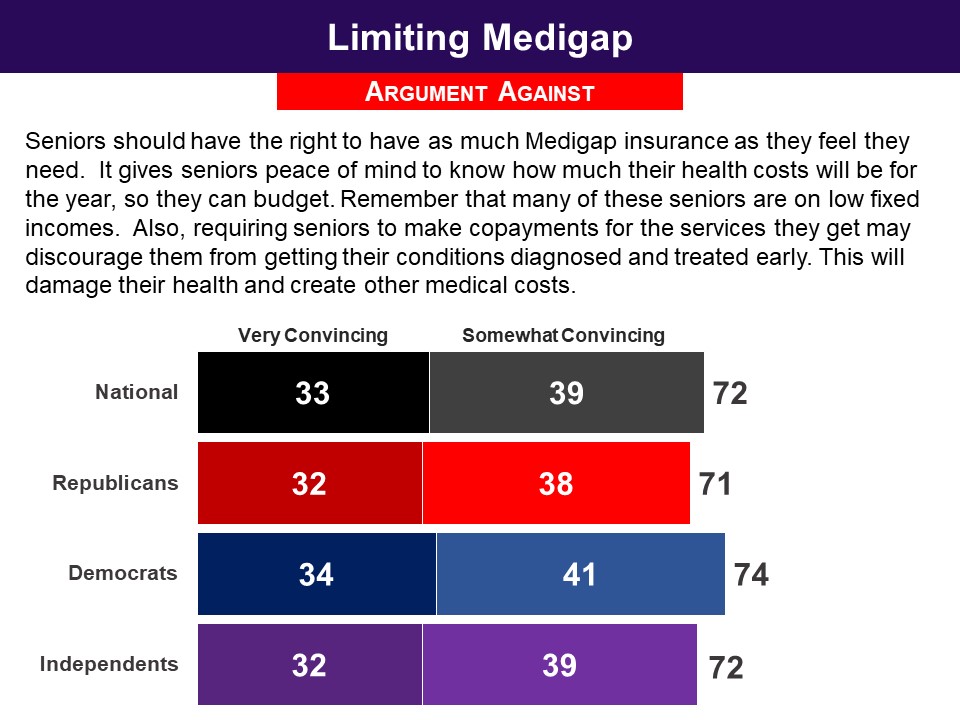

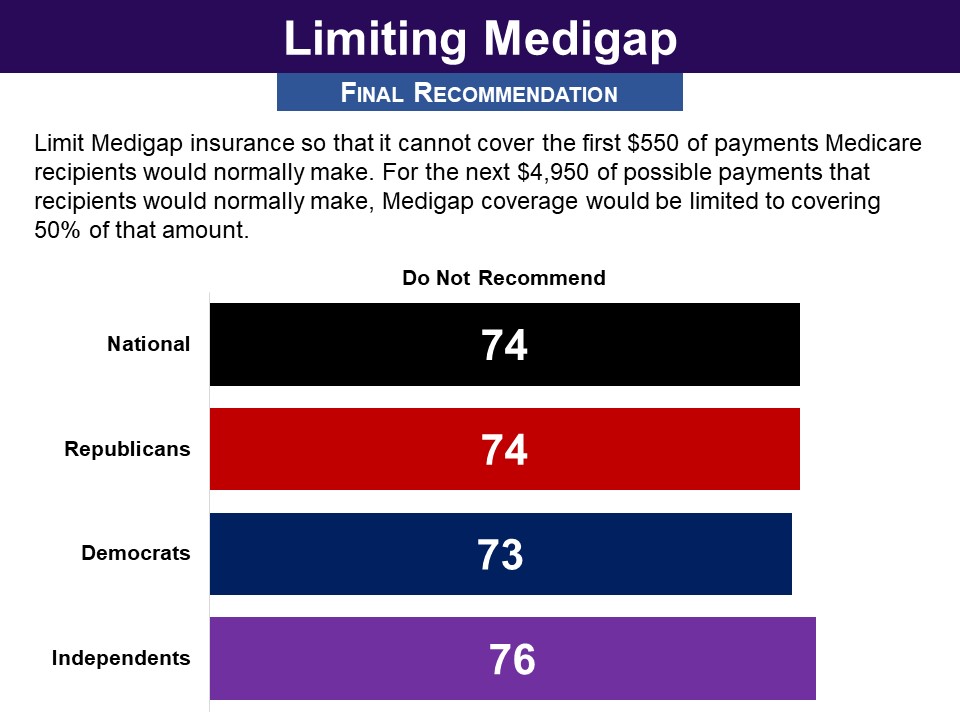

Respondents were presented a proposal to reduce costs: This proposal concerns Medigap health insurance policies. Medigap is extra health insurance that Medicare recipients can buy from a private company to pay health care costs not covered by Medicare. Medicare recipients ordinarily do pay deductibles and copayments. However, with a Medigap policy typically they do not. Research has shown that when seniors have Medigap insurance, and do not have to pay deductibles and copayments, they do go to the doctor more often, which costs Medicare more money. A proposal that could save Medicare money would be to limit how much Medigap plans can eliminate the payments for deductibles and copayments. The aim is to encourage Medicare recipients to be more restrained in using medical services. More specifically, the proposal is to limit Medigap insurance so that it cannot cover the first $550 of payments Medicare patients would normally make. For the next $4,950 of possible payments that Medicare patients would normally make, Medigap coverage would be limited to covering 50% of that amount. It is estimated that this proposal would create savings that would cover 10% of the shortfall (saving on average $23 billion a year). When they evaluated arguments for and against the proposal, both arguments were found convincing by bipartisan majorities, but the argument against did substantially better. The argument in favor was found convincing by 54%. The argument against was found convincing by (72%). |

|

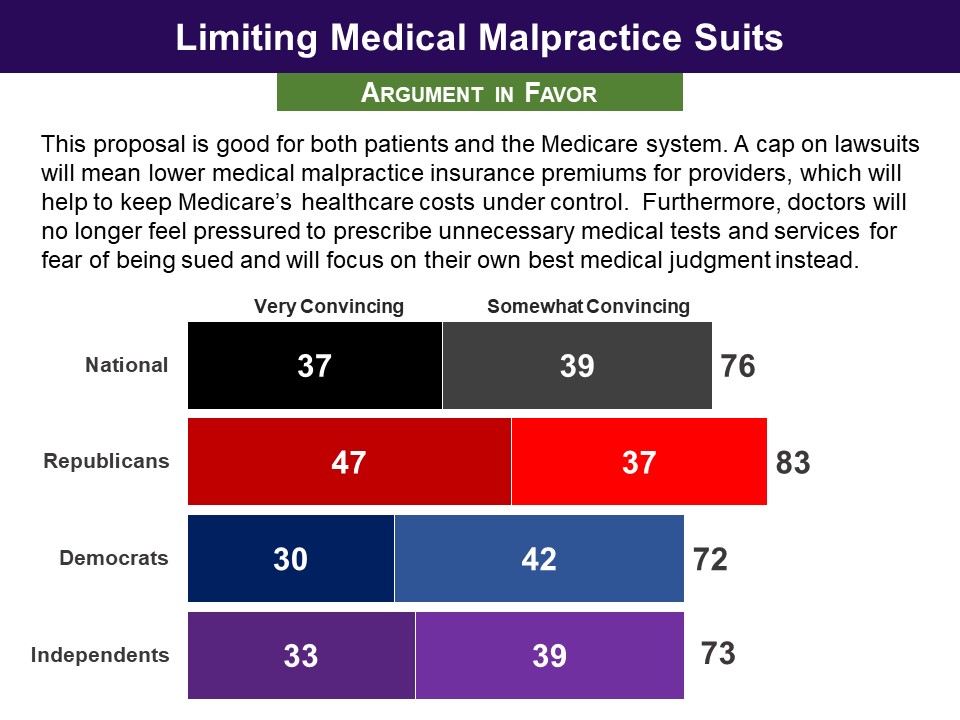

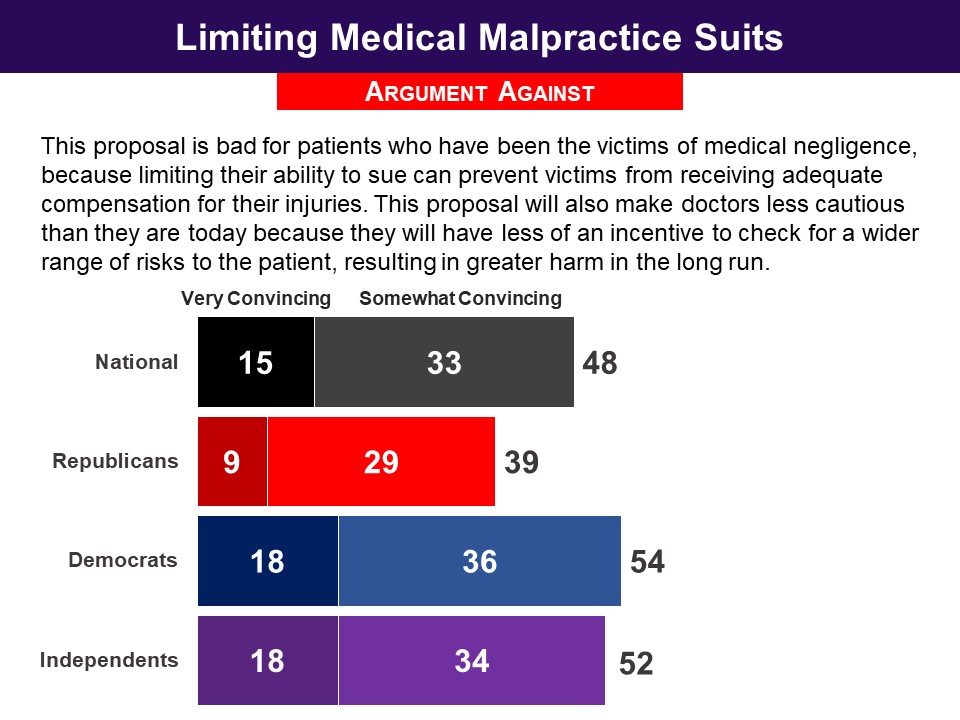

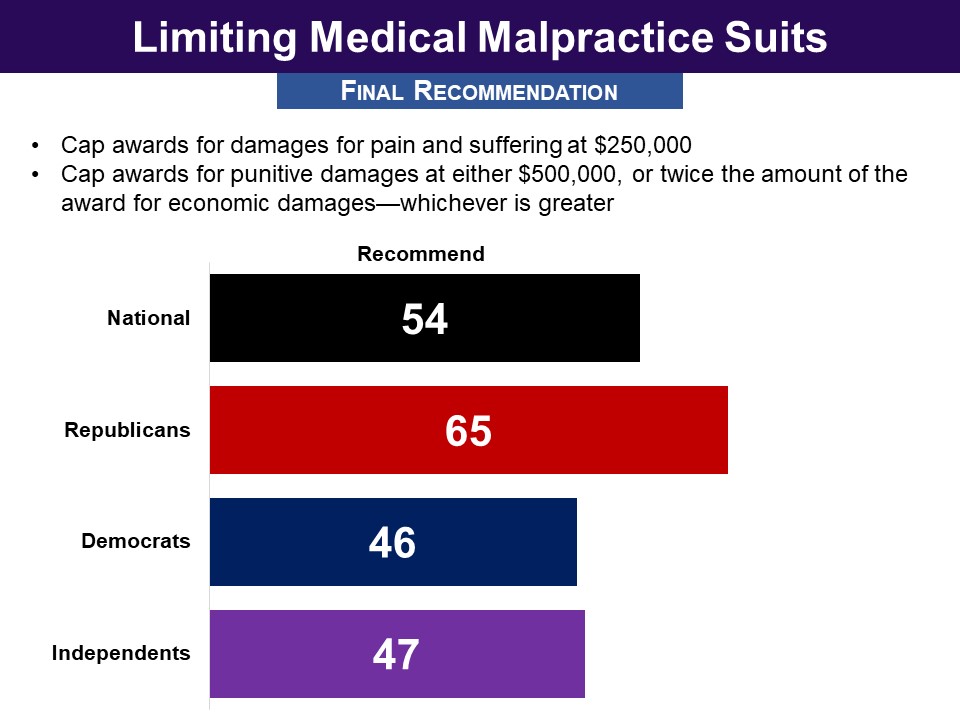

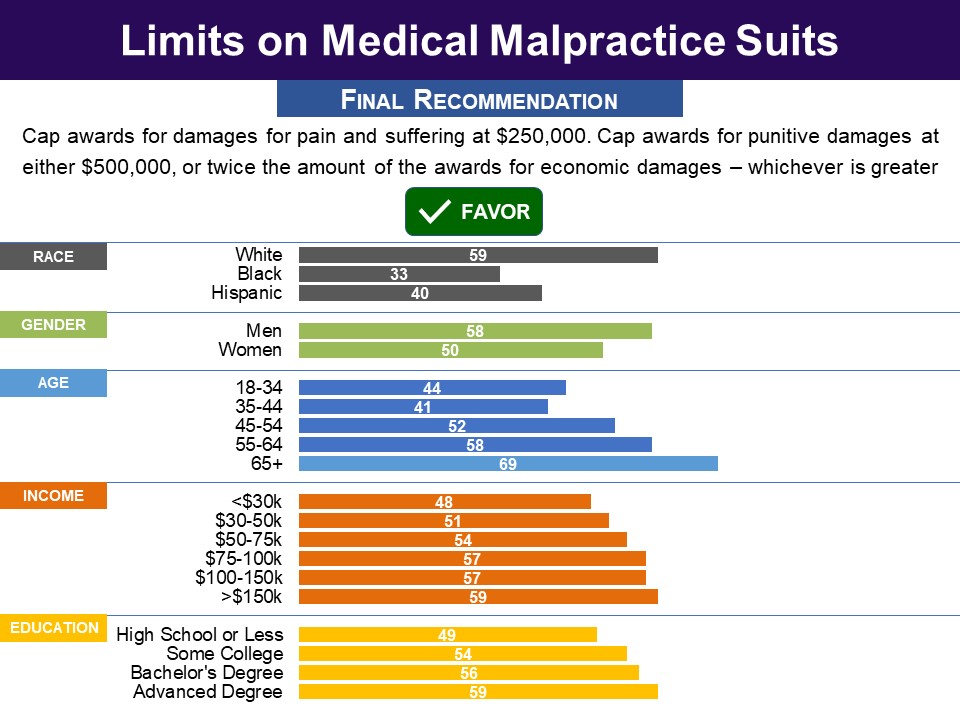

Respondents were presented a proposal to reduce costs: Another proposal for reducing costs would be to limit medical malpractice lawsuits, an idea that is also called “tort reform.” In recent years there has been an increase in the amount of medical malpractice awards that have led to higher malpractice insurance premiums for doctors. These costs have been passed on to patients in the form of higher medical fees. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has concluded that putting limits on malpractice awards would lead to reduced medical fees, which would also help Medicare. One proposal is to:

This option is estimated to bring about changes that cover 4% of the shortfall (saving Medicare an average of $9 billion a year). When they evaluated arguments for and against the proposal, the argument in favor did substantially better than the argument against. The argument in favor was found convincing by 76% overall. The argument against was found convincing by less than half (48%). In their final recommendations, 54% chose the proposal to place limits on medical malpractice suits, covering 4 percent of the shortfall, but this was not bipartisan: it was chosen by 65% of Republicans, but only 46% of Democrats (54% opposed). |

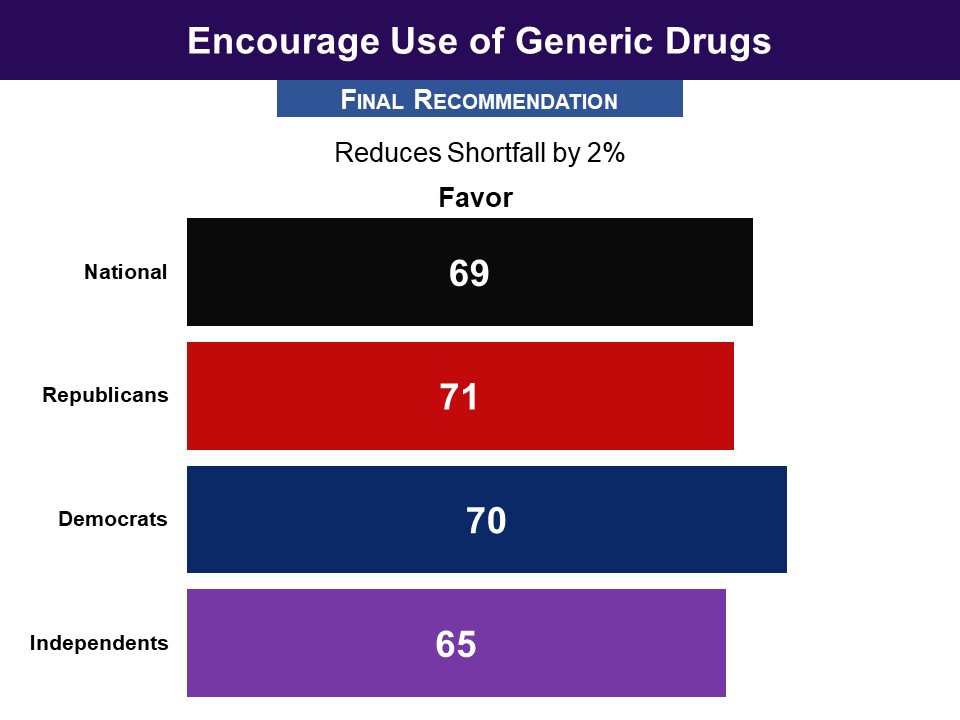

In the end, asked to make their final recommendations, adopting the proposal on generics was recommended by a highly bipartisan seven‐in‐ten majority, with minimal partisan differences.

In the end, asked to make their final recommendations, adopting the proposal on generics was recommended by a highly bipartisan seven‐in‐ten majority, with minimal partisan differences.

Response Without Undergoing Policymaking Simulation

Response Without Undergoing Policymaking Simulation

When asked for their final recommendation, seven in ten recommended that drug companies should receive at least 17 percent less money, including 68% of Republicans and 70% of Democrats. Forty two percent went further and wanted them to receive 20 percent less money, including 38% of Republicans and just less than half of Democrats (47%).

When asked for their final recommendation, seven in ten recommended that drug companies should receive at least 17 percent less money, including 68% of Republicans and 70% of Democrats. Forty two percent went further and wanted them to receive 20 percent less money, including 38% of Republicans and just less than half of Democrats (47%).

While the proposal to give drug companies 20 percent less money was not recommended by a majority, a large bipartisan majority did find the idea at least tolerable. Asked to assess its acceptability using a 0-10 scale, with 5 being “just tolerable”, 83% found the idea at least tolerable (5-10), including 81% of Republicans and 87% of Democrats.

While the proposal to give drug companies 20 percent less money was not recommended by a majority, a large bipartisan majority did find the idea at least tolerable. Asked to assess its acceptability using a 0-10 scale, with 5 being “just tolerable”, 83% found the idea at least tolerable (5-10), including 81% of Republicans and 87% of Democrats.

In the end, the option to equalize what hospitals and doctors’ offices receive for providing some services to Medicare was recommended by 56% nationally, and among both Republicans and Democrats.

In the end, the option to equalize what hospitals and doctors’ offices receive for providing some services to Medicare was recommended by 56% nationally, and among both Republicans and Democrats.

Response Without Undergoing Policymaking Simulation

Response Without Undergoing Policymaking Simulation

When they evaluated arguments for and against the proposal, the argument in favor did substantially better. The argument in favor of a payroll tax increase was found convincing by eight in ten (79%). The argument against was found convincing by just half.

When they evaluated arguments for and against the proposal, the argument in favor did substantially better. The argument in favor of a payroll tax increase was found convincing by eight in ten (79%). The argument against was found convincing by just half.

When asked for their final recommendations, 67% chose to increase the payroll tax by at least 0.1 percent, with similar majorities among both Republicans (69%) and Democrats (68%). A hike of 0.2 or more was chosen by 41% (Republicans 42%, Democrats 41%). And the 0.3 percent hike by just 20%, with similar shares among partisans.

When asked for their final recommendations, 67% chose to increase the payroll tax by at least 0.1 percent, with similar majorities among both Republicans (69%) and Democrats (68%). A hike of 0.2 or more was chosen by 41% (Republicans 42%, Democrats 41%). And the 0.3 percent hike by just 20%, with similar shares among partisans.

Interestingly, though less than half favored a greater increase, large majorities said they would find it tolerable. Asked to rate the acceptability of a 0.2 percent increase using a 0-10 scale, with 5 being “just tolerable,” 71% found it at least tolerable (5-10) (Republicans 69%, Democrats 75%,). The 0.3 percent increase was found at least tolerable by 59% (Republicans 57%, Democrats 63%).

Interestingly, though less than half favored a greater increase, large majorities said they would find it tolerable. Asked to rate the acceptability of a 0.2 percent increase using a 0-10 scale, with 5 being “just tolerable,” 71% found it at least tolerable (5-10) (Republicans 69%, Democrats 75%,). The 0.3 percent increase was found at least tolerable by 59% (Republicans 57%, Democrats 63%).

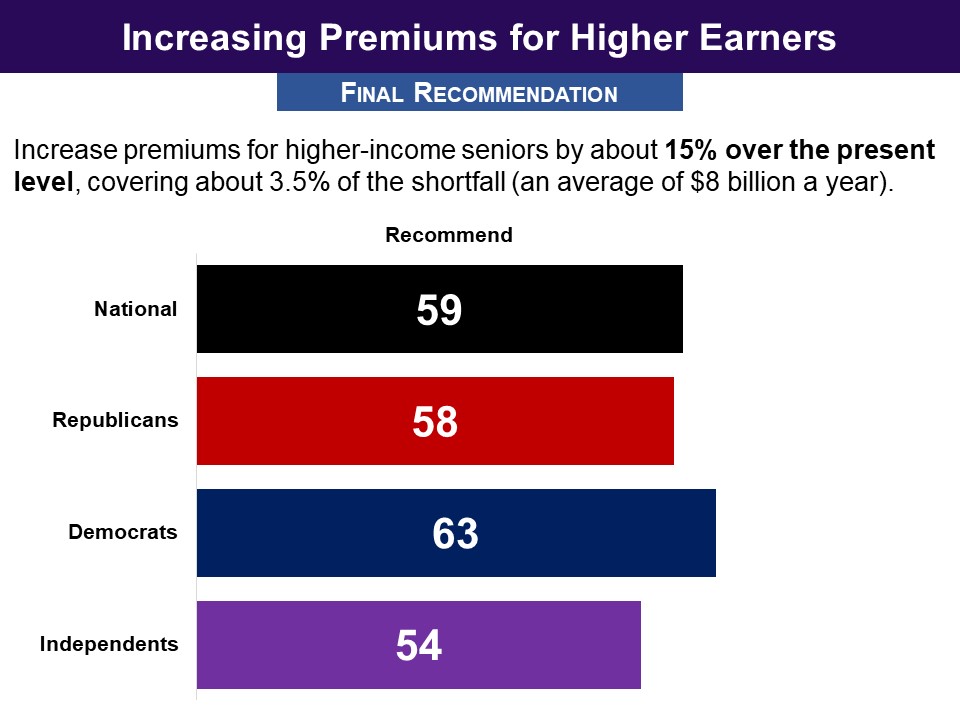

They were told that, “A 15% increase would cover 3.5% of the shortfall, while a 30% increase would cover 7% of the shortfall.”

They were told that, “A 15% increase would cover 3.5% of the shortfall, while a 30% increase would cover 7% of the shortfall.”

In the end, an overall majority of 59% recommended a 15 percent or more increase in premiums for higher incomes (Republicans 58%, Democrats 63%). Interestingly, respondents with incomes above $150,000 were just as supportive of this 15% increase as the full sample.

In the end, an overall majority of 59% recommended a 15 percent or more increase in premiums for higher incomes (Republicans 58%, Democrats 63%). Interestingly, respondents with incomes above $150,000 were just as supportive of this 15% increase as the full sample.

Only a quarter recommended a 30 percent increase, but when asked to rate how acceptable the proposal would be using a 0-10 scale, it was found at least tolerable (5-10) by 69% (Republicans 66%, Democrats 75%).

Only a quarter recommended a 30 percent increase, but when asked to rate how acceptable the proposal would be using a 0-10 scale, it was found at least tolerable (5-10) by 69% (Republicans 66%, Democrats 75%).

In the end, no group had a majority recommending an increase to standard premiums. Asked to choose between increasing standard premiums to cover 30 percent or 35 percent of total costs, 58% did not choose either option, including 56% of both Republicans and Democrats, and 64% of independents.

In the end, no group had a majority recommending an increase to standard premiums. Asked to choose between increasing standard premiums to cover 30 percent or 35 percent of total costs, 58% did not choose either option, including 56% of both Republicans and Democrats, and 64% of independents.

But, asked to rate how acceptable the proposal to raise premiums to cover 30 percent of Medicare’s costs would be using a 0-10 scale, 57% found it at least tolerable (5-10) , including 57% of Republicans and 60% of Democrats.

But, asked to rate how acceptable the proposal to raise premiums to cover 30 percent of Medicare’s costs would be using a 0-10 scale, 57% found it at least tolerable (5-10) , including 57% of Republicans and 60% of Democrats.

In their final recommendations, only 26% chose the option of limiting Medigap insurance; and there were no partisan differences. Three quarters rejected the proposal (74%), including 74% of Republicans and 73% of Democrats.

In their final recommendations, only 26% chose the option of limiting Medigap insurance; and there were no partisan differences. Three quarters rejected the proposal (74%), including 74% of Republicans and 73% of Democrats.

Asked to assess how acceptable the proposal would be using a 0-10 scale, a bare majority of 52% found it at least tolerable (5-10), including 54% of Republicans and 52% of Democrats.

Asked to assess how acceptable the proposal would be using a 0-10 scale, a bare majority of 52% found it at least tolerable (5-10), including 54% of Republicans and 52% of Democrats.

However, asked to assess how acceptable the proposal would be using a 0-10 scale, it was found at least tolerable (5-10) by 68% of Democrats as well 81% of Republicans and 73% overall.

However, asked to assess how acceptable the proposal would be using a 0-10 scale, it was found at least tolerable (5-10) by 68% of Democrats as well 81% of Republicans and 73% overall.