Sentencing Reform

For some time now there has been a substantial debate about the high level of incarceration in the United States. Since the 1980s the number of Americans in prison has quadrupled and is greater than any other country in absolute terms and on a per capita basis. Much of this increase has been due to mandatory sentencing laws that were established starting in the 1980s.

In 2017 two major pieces of legislation were proposed which sought to reduce mandatory minimum sentences and give judges more discretion in sentencing — the First Step Act (S. 3649 by Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and the Smarter Sentencing Act (S. 1933) by Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT). These were the basis of the PPC survey explored below.

In 2018, a limited version of the First Step Act (S. 756) by Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-AK) was passed into law.

Provisions not passed into law were subsequently incorporated into a new bill called The Next Step Act, sponsored by Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-NJ) (H.R. 1893) and Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) (S. 697). The Smarter Sentencing Act did not pass and was reintroduced by Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) (S. 2850).

Below are provisions from the Smarter Sentencing Act and what is now the Next Step Act, that received bipartisan support.

- National Sample: 2,417 registered voters

- Margin of Error: +/- 2.0%

- Fielded: July 10 - 23, 2018

- Questionnaire with Frequencies

The survey covered major provisions from the original version of the First Step and also the Smarter Sentencing Act.

Proposals with bipartisan support that have not become law and are discussed below include:

- Reducing the mandatory minimum sentences for one-strike federal drug offenses

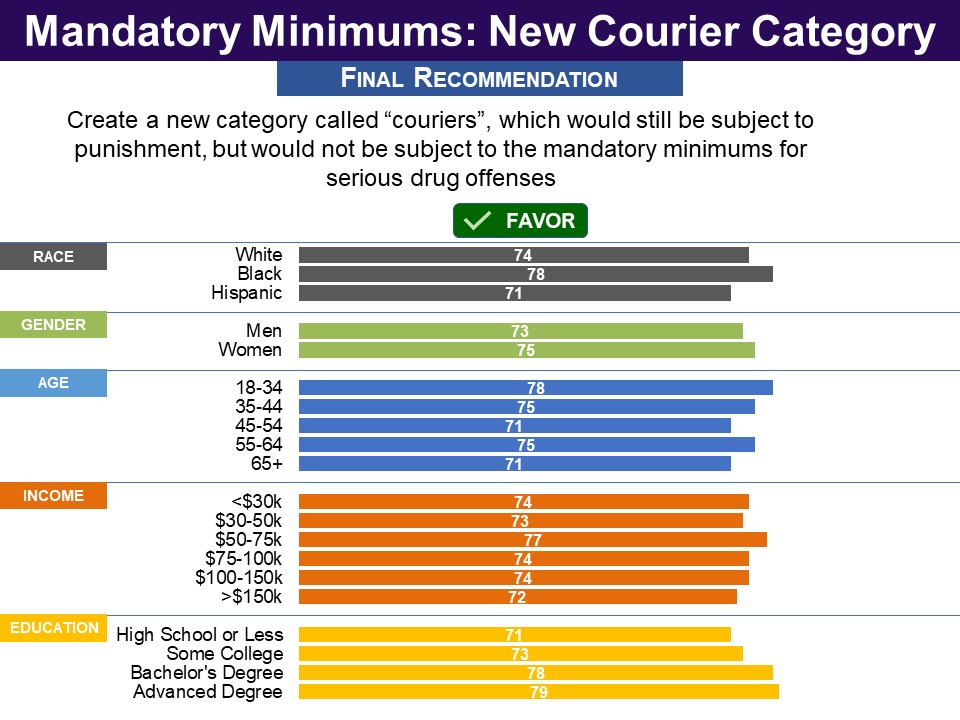

- Creating a new sentencing category for those who store or transport illegal drugs or drug money, that comes with no mandatory sentence

- Giving judges discretion to release early prisoners who were convicted as juveniles and who have completed at least 20 years of their sentence

Proposals explored in the study that became law (and also received bipartisan support) include:

- Reducing the mandatory minimum sentences for two- and three-strike federal drug offenses

- Giving judges discretion to release early prisoners who are at least 60 years old and have served two thirds of their sentence; require assisted living; and/or are terminally ill

- Giving judges discretion to allow certain low-risk prisoners serve the last 10% of their sentence in a monitored home setting

- Retroactively applying the 2010 crack cocaine sentencing reforms

There were no proposals explored in the study that failed to receive bipartisan support.

|

REDUCING MANDATORY MINIMUM SENTENCING |

|

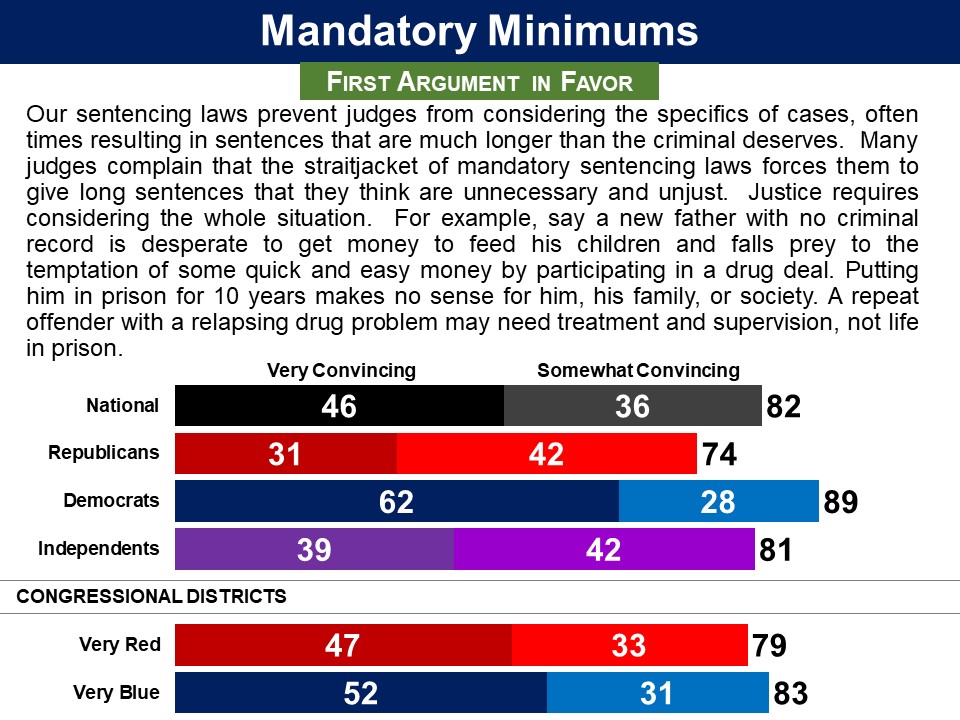

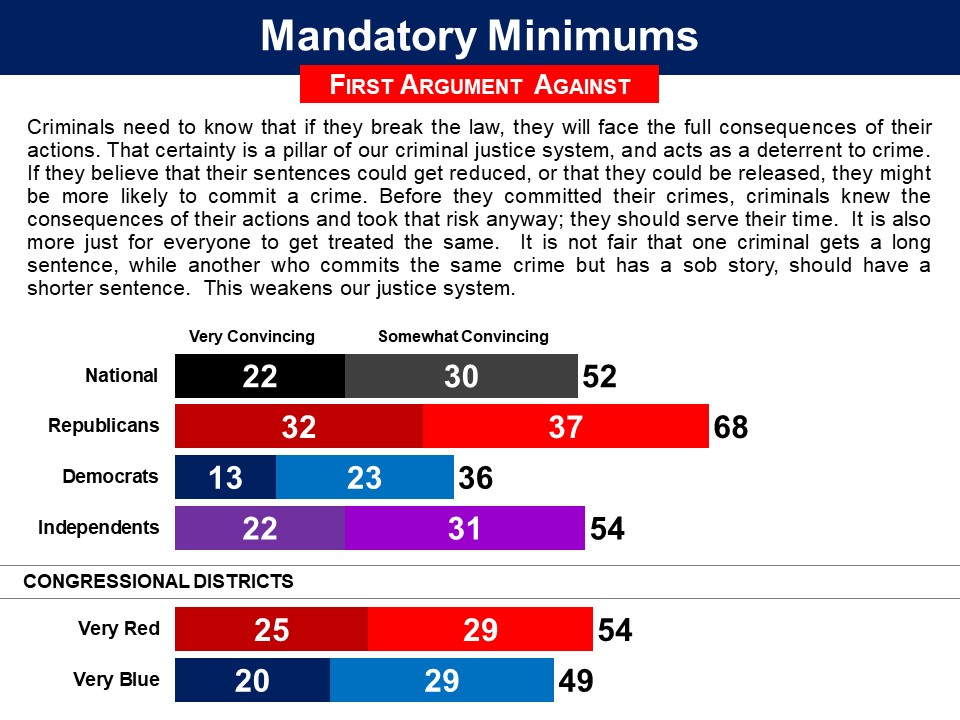

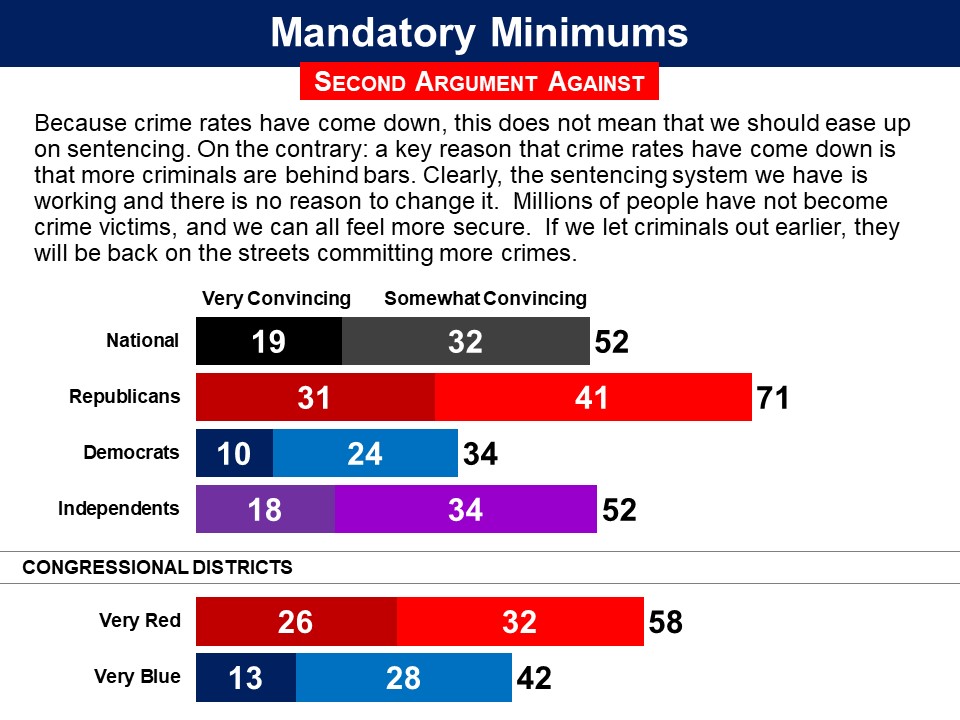

Current legislative proposals would reduce mandatory minimum sentences for a first federal drug offense, and reduce the mandatory minimum sentence for those convicted of transporting or storing illegal drugs or drug money. These proposals presented to respondents were based on the Smarter Sentencing Act (S. 1933). Respondents were given a briefing about the increase of the incarcerated population and the major reasons for this increase. They were shown a graph of the incarcerated population in the US from the early 1900’s to 2015, and were told that roughly one percent of the US adult population is currently incarcerated. They were then shown the change in crime rates over the last several decades, which peaked in 1980’s and 90’s, and has since decreased. They were then told that: A major reason for the high rate of imprisonment is that during the period that crime rates were higher, a number of laws were passed that changed the way that sentencing was done at the federal and at the state level. This led to more people being imprisoned and to longer prison sentences. These laws required minimum sentences for specific crimes that were longer than the average sentences before such laws were enacted. They also reduced the options for judges to grant parole or early release. Thus, the length of time people spent in prison increased. A graph showing the increase of the average length of prison sentences since the mid-20th century was provided. Finally, they were informed that, “A major part of the increase in federal imprisonment has been an increase in arrests for the sale, trafficking or manufacturing of illegal drugs.” A graph showing the increase in the percent of federal prisoners that are drug offenders was provided. Several proposals for reforming federal mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses were then introduced: “One Strike” “Two Strikes” “Three Strikes” They then evaluated a series of general arguments for and against reducing mandatory minimum sentencing, and giving judges greater discretion to decide prison sentences. The pro arguments were generally found convincing by a much larger and more bipartisan majority than the con arguments. The argument which emphasized that mandatory minimum sentences for non-violent criminals are unjust was found convincing by 82% (Republicans 74%, Democrats 89%). The counter argument that relaxing mandatory minimums will increase crime was found convincing by just over half, including seven in ten Republicans but just over a third of Democrats.

Status of Legislation These two proposals were also in the Smarter Sentencing Act, sponsored by Sen. Mike Lee (R) in the 116th Congress, which was reintroduced by Sen. Dick Durbin (D) in the 117th Congress (S. 1013). The proposals to reduce mandatory sentences for two-strike federal drug offenses from 20 to 15 years, and reduce it for three-strike federal drug offenses from life in prison to 25 years, were in the First Step Act (S. 756), sponsored by Rep. Dan Sullivan (R) in the 115th Congress, which became law in December 2018. It passed the House 358-36, with 182 Republicans and 176 Democrats voting in favor, and 36 Republicans voting against. It passed the Senate 87-12, with 38 Republicans, 47 Democrats and 2 independents voting in favor, and 12 Republicans voting against. |

|

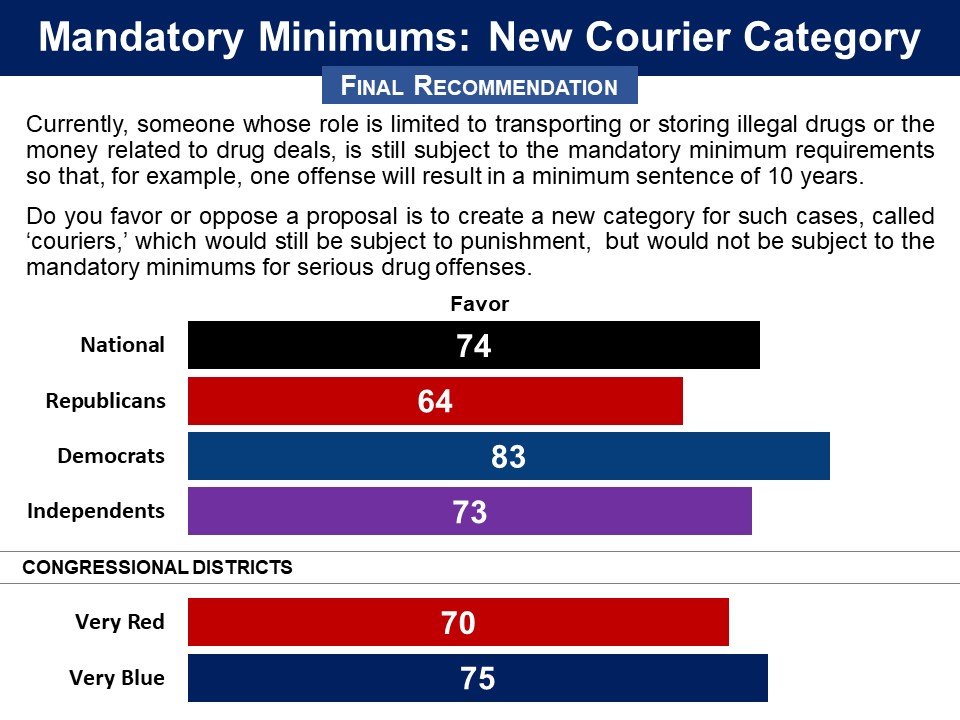

Creating a new category, with no mandatory minimum sentences, for someone whose role is limited to transporting or storing illegal drugs or money related to drug deals, was recommended by 74%, including 64% of Republicans and 83% of Democrats. New ‘Courier’ Category The proposal is to create a new category for such cases, called ‘couriers,’ which would still be subject to punishment, but would not be subject to the mandatory minimums.

|

|

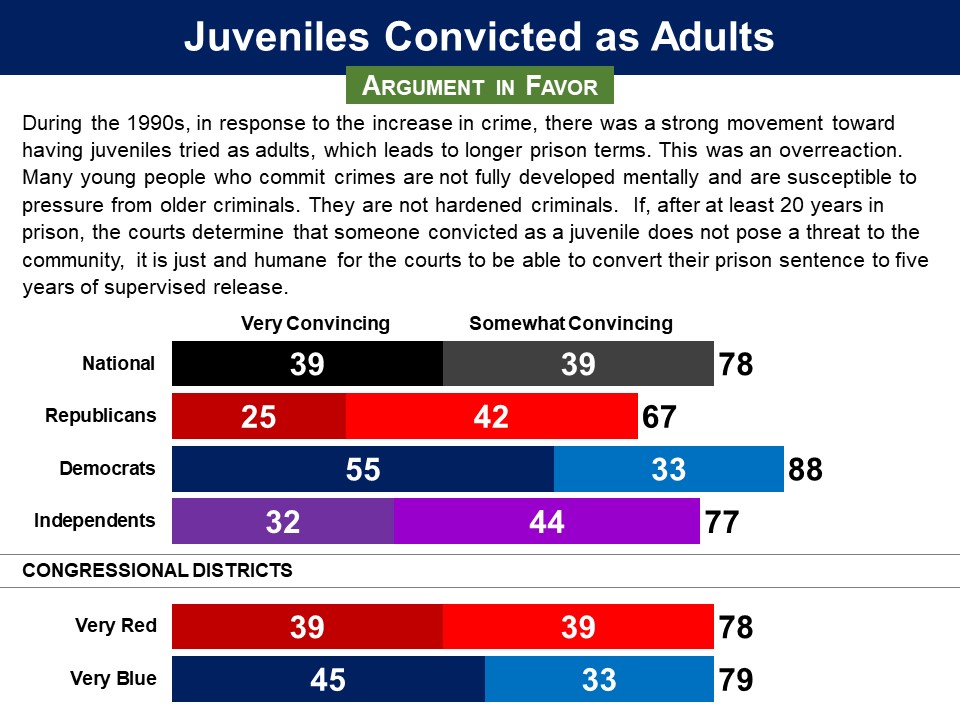

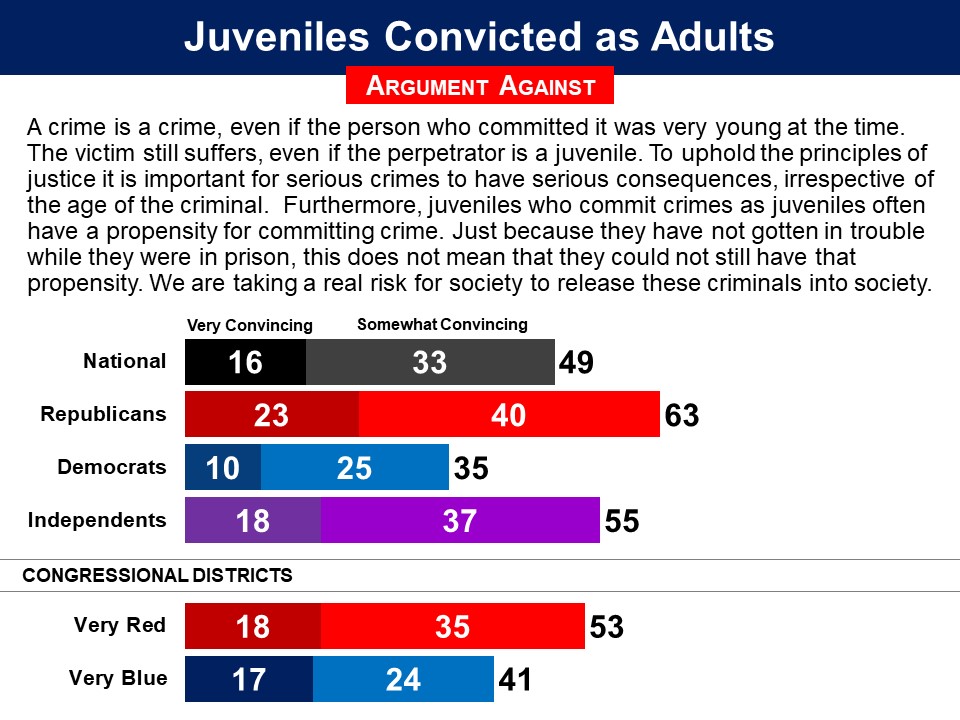

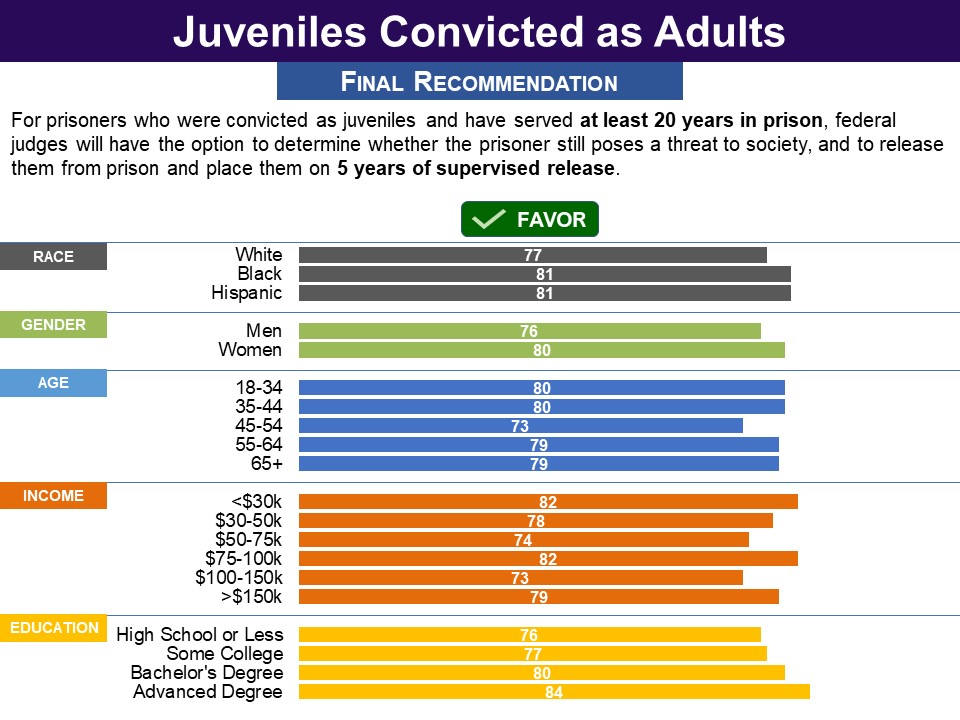

Current legislative proposals would allow judges to release early certain prisoners convicted as juveniles. The proposal presented to respondents was based on a provision in the Smarter Sentencing Act (S. 1933) from the 115th Congress. As mentioned above, respondents were first given a briefing on incarceration and sentencing in the US, evaluated arguments for and against reducing mandatory minimum sentences, and evaluated proposals for reducing mandatory minimums. Respondents were then introduced to the topic of juveniles who were convicted as adults, as follows: Some of the people in federal prison today were convicted for crimes they committed when they were juveniles i.e. less than 18 years old. Many of them were tried as adults and received long-term sentences, including life in prison. They were presented a proposal: For prisoners who were convicted as juveniles and have served at least 20 years in prison, federal judges will have the option to determine whether the prisoner still poses a threat to society, and to release them from prison and place them on 5 years of supervised release. Arguments for and against this proposal were evaluated. The argument in favor of the proposal did substantially better overall (78% convincing), than the con argument which was found convincing by just half (49%). However, both arguments were found convincing by similar majorities of Republicans. In the 117th Congress, this proposal is in the First Step Implementation Act of 2021 by Sen. Dick Durbin (D) (S. 1014). It has yet to make it out of committee. |

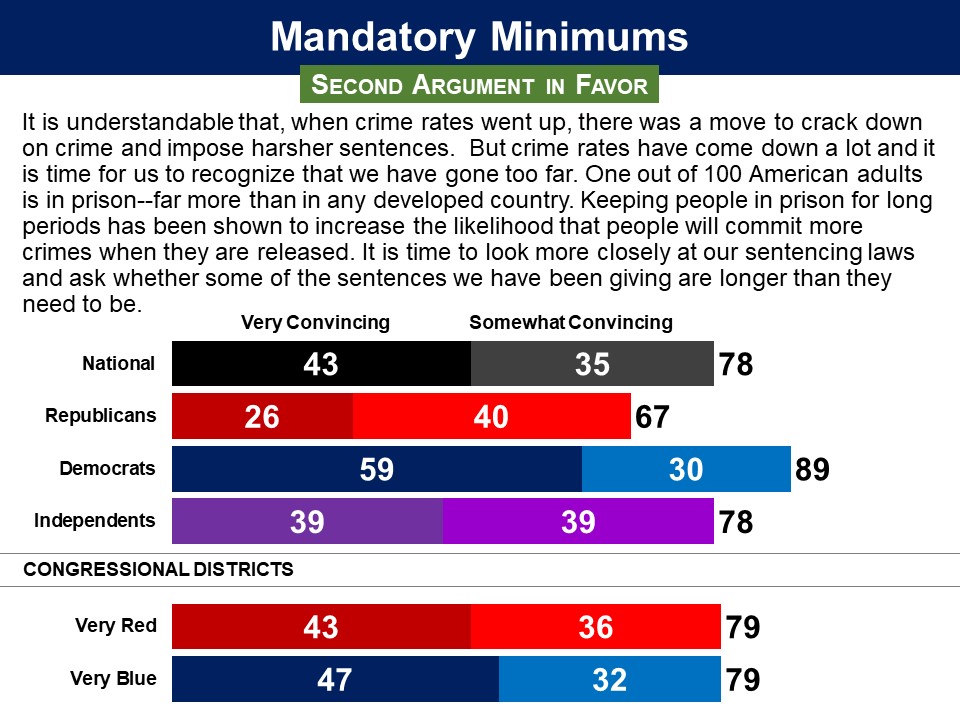

The argument that mandatory minimums were a response to increased crime, but since crime rates have dropped they have “overloaded our prison system”, was found convincing by 78%, including two thirds of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The counter argument, that if we reduce mandatory minimums the crime rate may increase, was found convincing by just over half, including seven in ten Republicans but just one third of Democrats.

The argument that mandatory minimums were a response to increased crime, but since crime rates have dropped they have “overloaded our prison system”, was found convincing by 78%, including two thirds of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The counter argument, that if we reduce mandatory minimums the crime rate may increase, was found convincing by just over half, including seven in ten Republicans but just one third of Democrats.

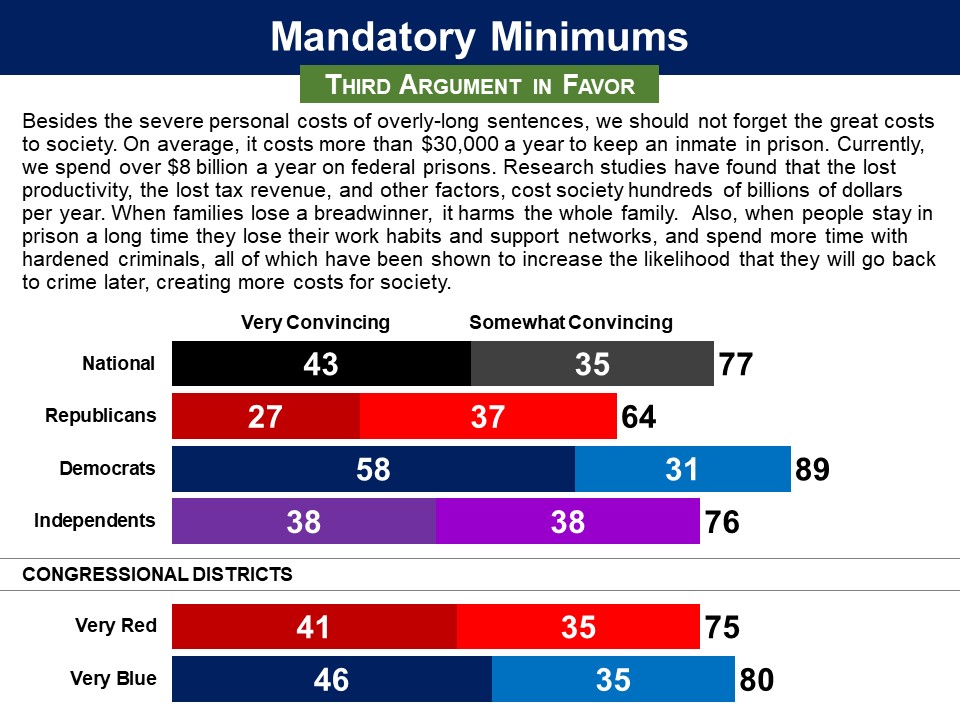

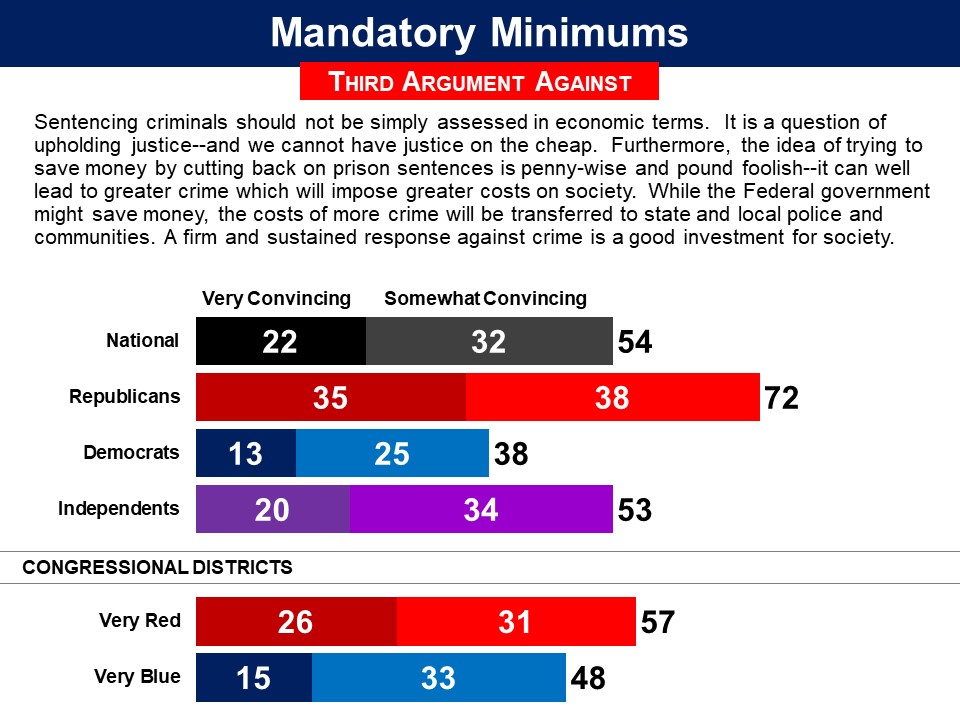

The argument that a large prison population is costly to society was found convincing by 77%, including two thirds of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The counter argument, that justice is not cheap, was found convincing by a modest majority of 54%, including seven in ten Republicans but just a third of Democrats.

The argument that a large prison population is costly to society was found convincing by 77%, including two thirds of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The counter argument, that justice is not cheap, was found convincing by a modest majority of 54%, including seven in ten Republicans but just a third of Democrats.

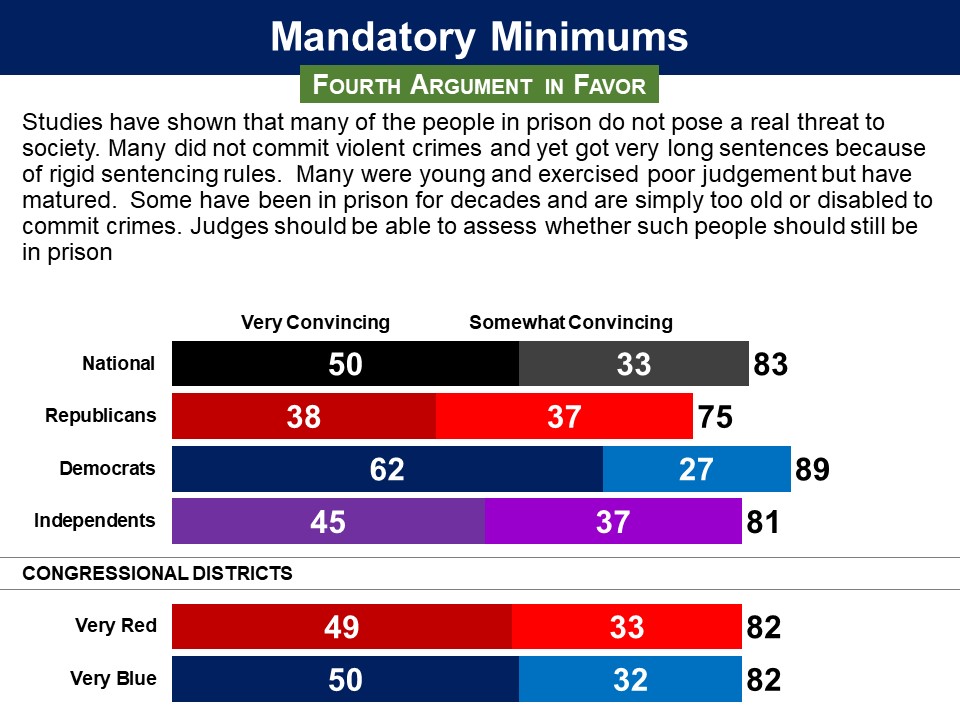

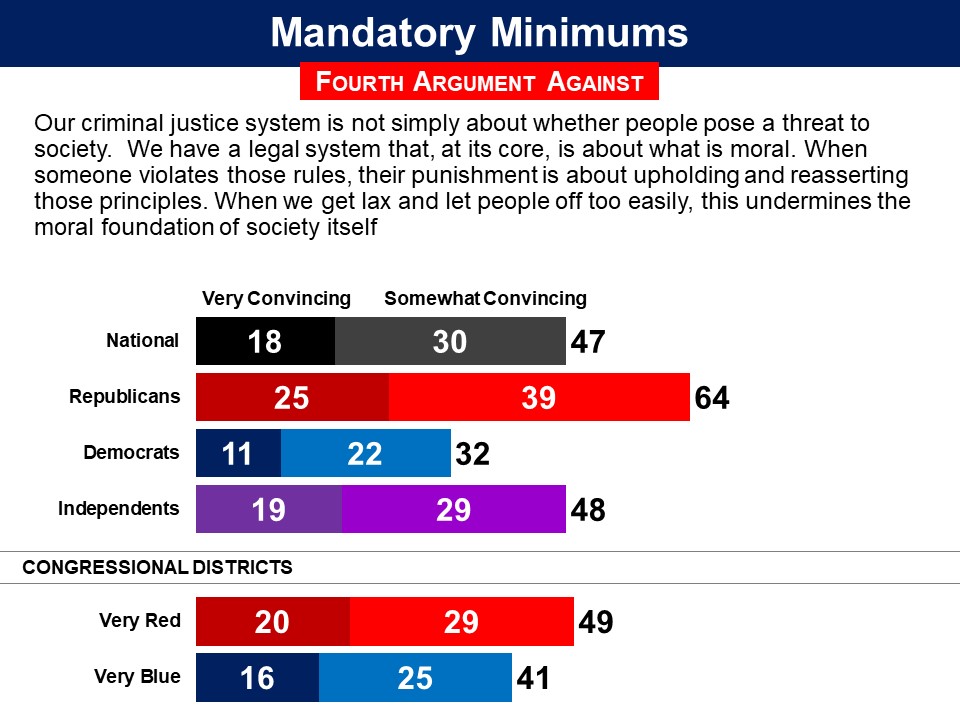

The argument that many prisoners do not pose a threat to society was found convincing by over eight in ten, including three quarters of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The counter argument, which asserted that prison sentences are not about the threat posed, but about upholding morals, was found convincing by less than half (47%), including just three in ten Democrats, but a majority of Republicans (64%).

The argument that many prisoners do not pose a threat to society was found convincing by over eight in ten, including three quarters of Republicans and nine in ten Democrats. The counter argument, which asserted that prison sentences are not about the threat posed, but about upholding morals, was found convincing by less than half (47%), including just three in ten Democrats, but a majority of Republicans (64%).

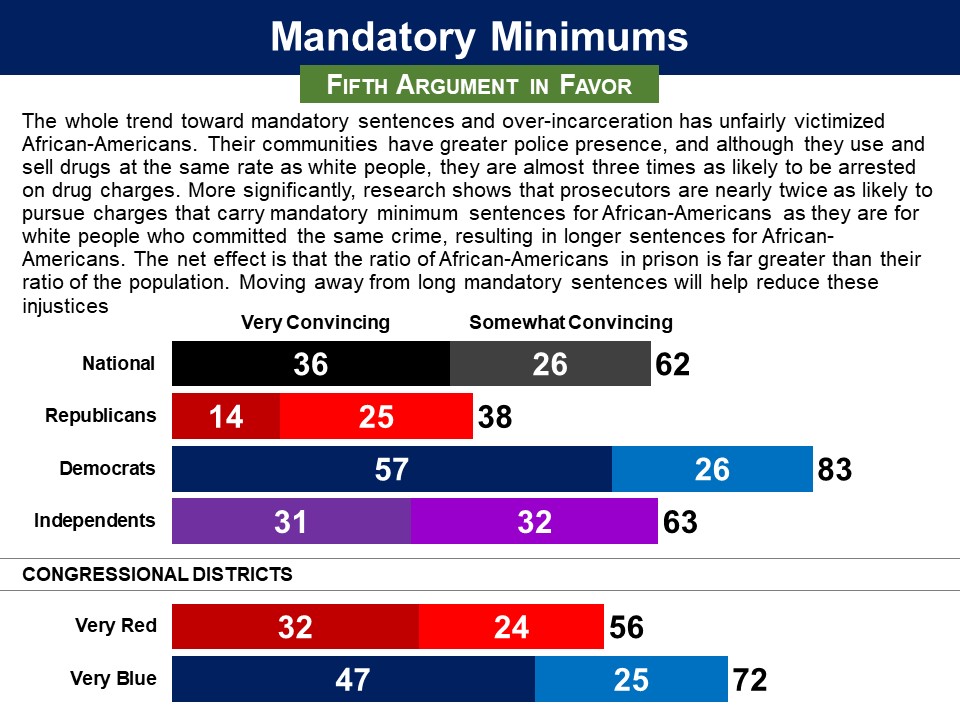

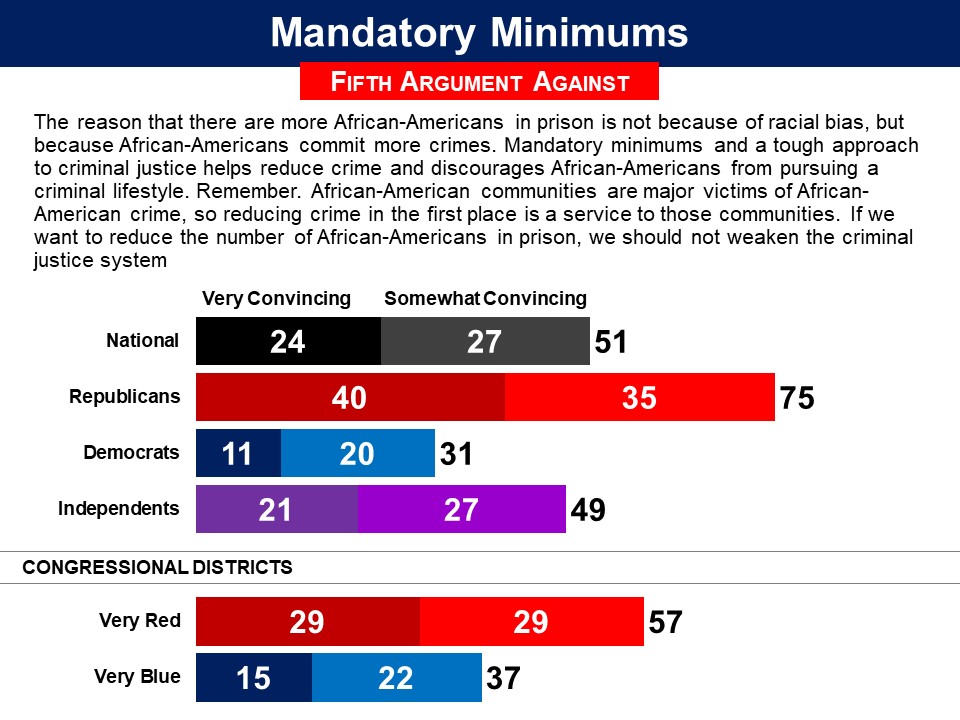

The argument that mandatory minimums have “unfairly victimized African‐Americans,” was the most polarizing argument in favor of reducing mandatory minimums. It was found convincing by 62% overall and 83% of Democrats, but just four in ten Republicans. The counter argument, that there is no racial bias, was found convincing by half, including three in four Republicans and just three in ten Democrats.

The argument that mandatory minimums have “unfairly victimized African‐Americans,” was the most polarizing argument in favor of reducing mandatory minimums. It was found convincing by 62% overall and 83% of Democrats, but just four in ten Republicans. The counter argument, that there is no racial bias, was found convincing by half, including three in four Republicans and just three in ten Democrats.

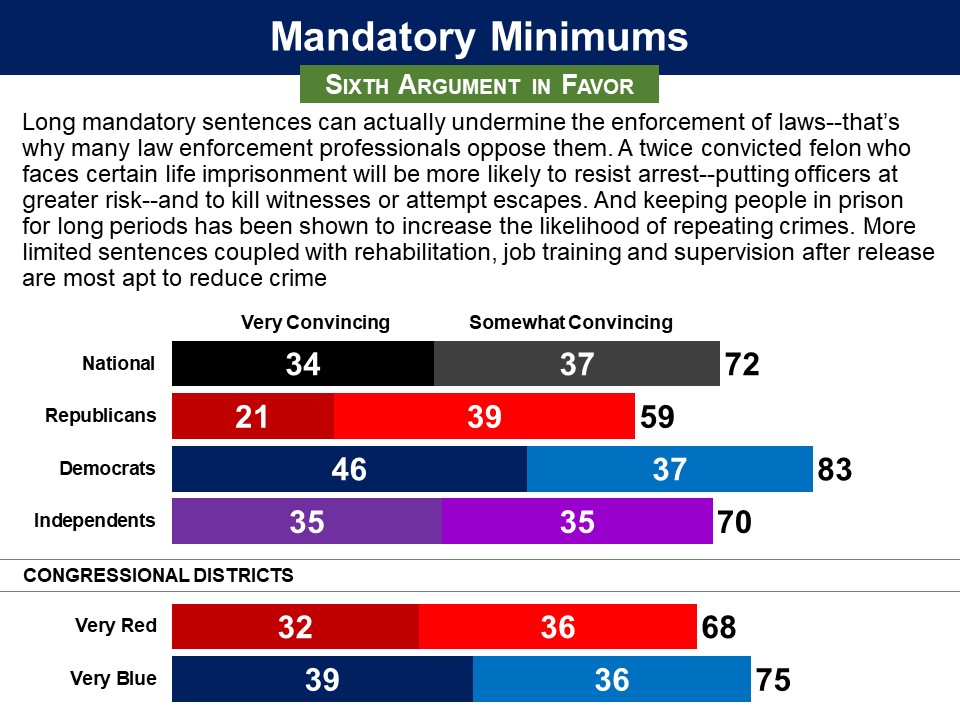

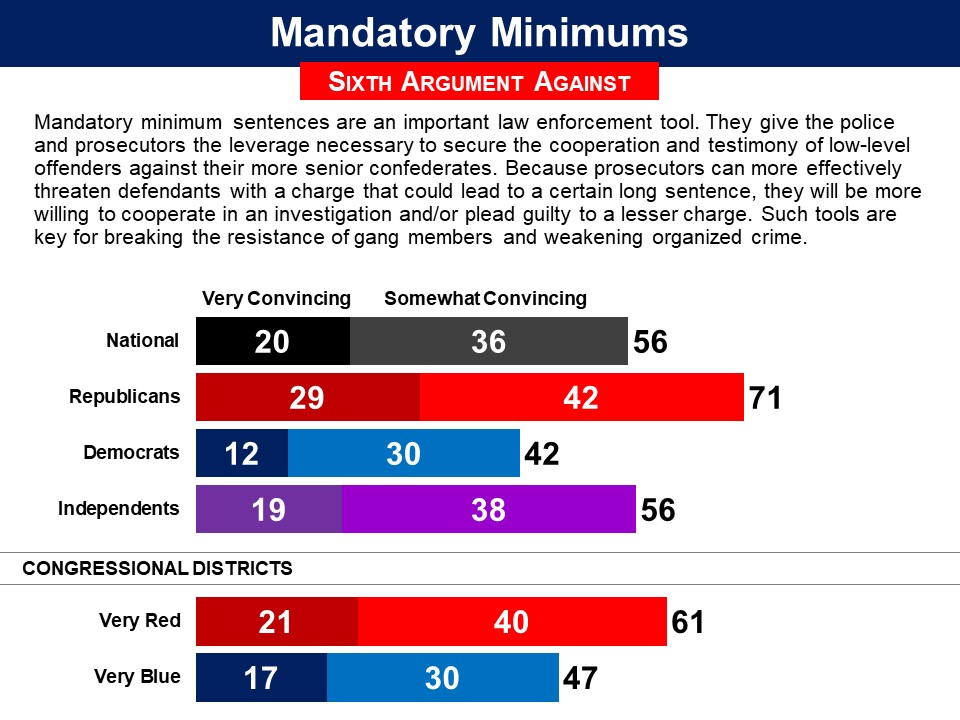

The argument that longer sentences is bad for law enforcement, in part because it increases chances of recidivism, was found convincing by seven in ten, including six in ten Republicans and over eight in ten Democrats. The counter argument, that they give law enforcement, “leverage necessary to secure the cooperation and testimony of low‐level offenders against their more senior confederates,” was found convincing by a majority of 56%, including seven in ten Republicans but just four in ten Democrats.

The argument that longer sentences is bad for law enforcement, in part because it increases chances of recidivism, was found convincing by seven in ten, including six in ten Republicans and over eight in ten Democrats. The counter argument, that they give law enforcement, “leverage necessary to secure the cooperation and testimony of low‐level offenders against their more senior confederates,” was found convincing by a majority of 56%, including seven in ten Republicans but just four in ten Democrats.

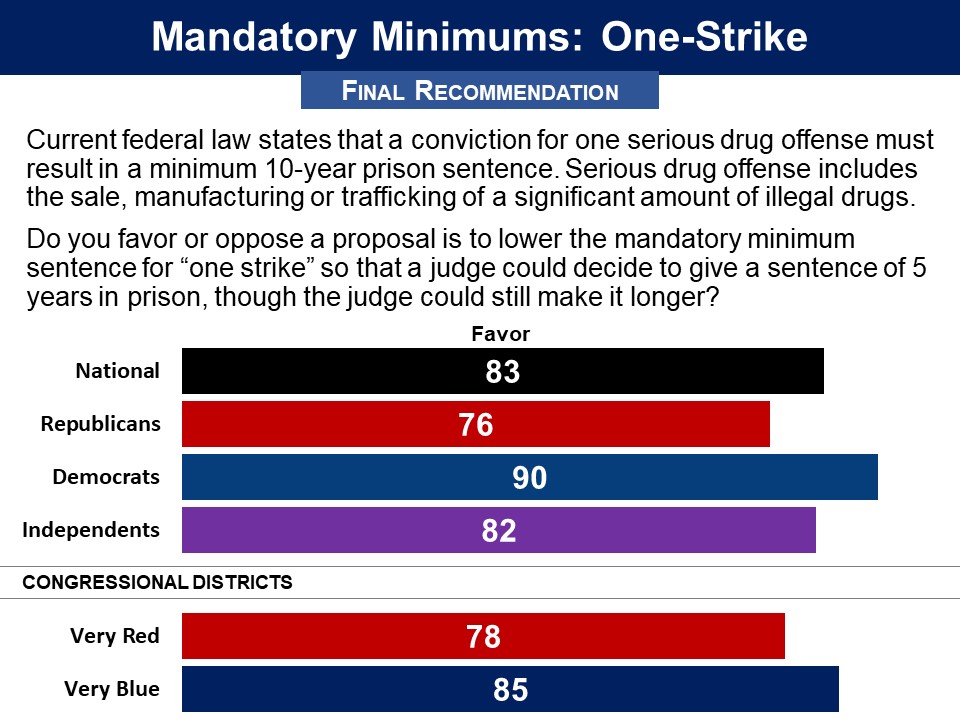

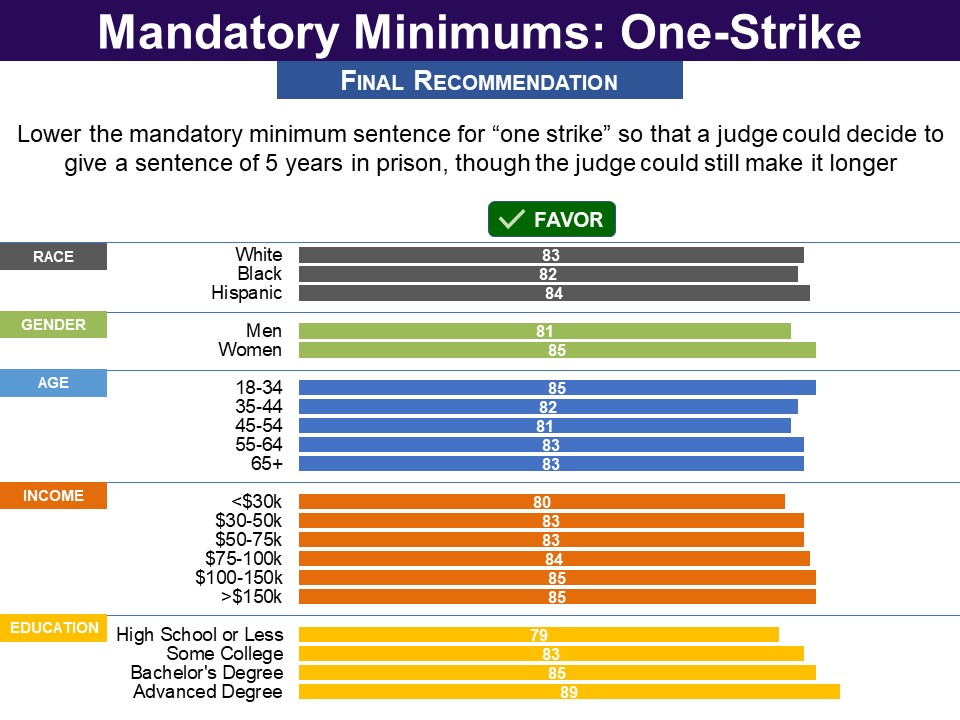

Finally, asked for their final recommendations, large bipartisan majorities recommended all of the proposals. Lowering the mandatory minimum of 10 years in prison to five years for one serious drug offense was recommended by 83%, including 76% of Republicans and 90% of Democrats.

Finally, asked for their final recommendations, large bipartisan majorities recommended all of the proposals. Lowering the mandatory minimum of 10 years in prison to five years for one serious drug offense was recommended by 83%, including 76% of Republicans and 90% of Democrats.

Related Standard Polls

Related Standard Polls

The two other proposals that have since passed into law were also approved. These include:

The two other proposals that have since passed into law were also approved. These include:

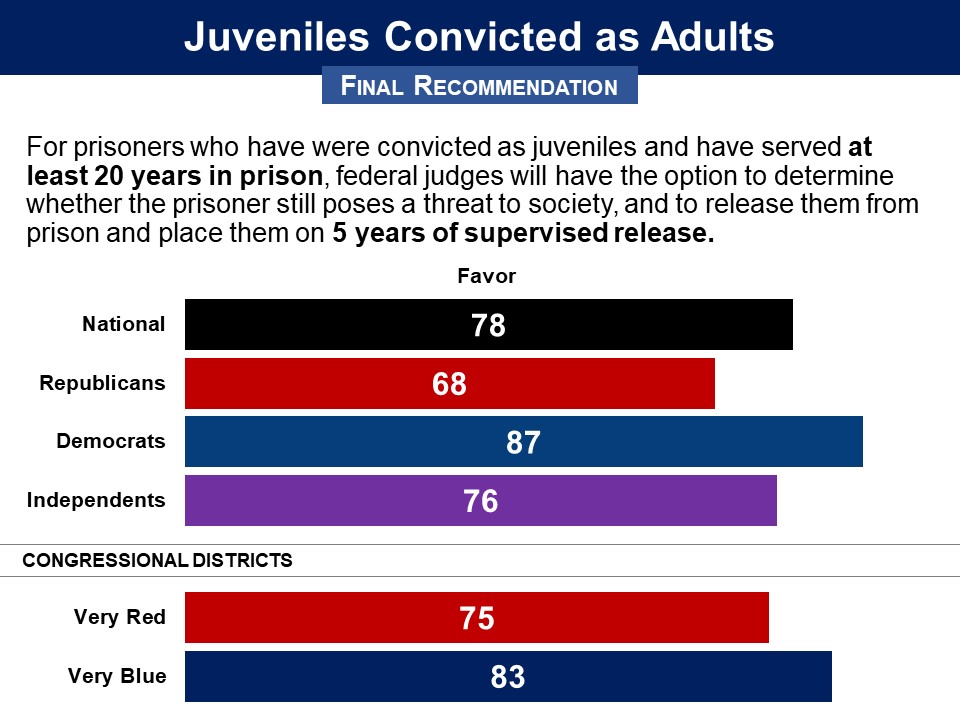

Finally, asked for their final recommendation, 78% favored the proposal, including 68% of Republicans and 87% of Democrats.

Finally, asked for their final recommendation, 78% favored the proposal, including 68% of Republicans and 87% of Democrats.

Status of Legislation

Status of Legislation